‘Deaf people can love music as much as anybody’

BBC/Sisi Burn

BBC/Sisi BurnConversations between Ludwig van Beethoven and his friends are being used for a British Sign Language exploration of his Ninth Symphony, 200 years on from its premiere.

Ludwig van Beethoven debuted his Ninth Symphony, widely regarded as one of the masterpieces of Western classical music, in 1824 as he was losing his hearing.

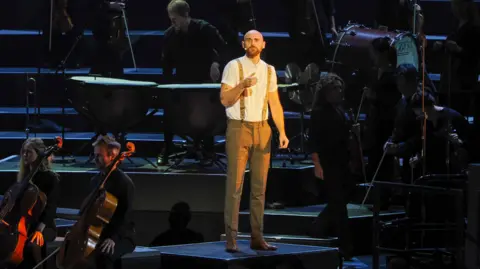

To celebrate 200 years since its debut, actors at this year’s BBC Proms performed a British Sign Language (BSL) exploration of the piece, followed by the Aurora Orchestra playing the symphony from memory.

Rhiannon May, a deaf actor who plays Beethoven in the performance, explains why it is important to make the symphony accessible for both deaf and hearing people: “Often it’s seen that deaf people and music don’t really go together, but that’s just not true.

“I think deaf people can love music as much as anybody,” she adds.

Rhiannon says the tactile and visual elements of the performance is what she focuses on “that’s what I go to as a deaf person, I’m not necessarily thinking about the sounds.”

But as the basses and drums come in, she can feel it through her feet: “You can feel it reverberating through you because it’s so powerful.”

The performance, which airs on BBC Four on Friday 30 August at 20:00 BST, is in two halves.

The first sees the symphony split into its four movements. Each section starts with Rhiannon and actor and interpreter Thomas Simper enacting extracts from Beethoven’s conversation books – notepads he carried to converse with his friends as he was losing his hearing.

In the second half, the full symphony is performed by the Aurora Orchestra from memory, a feat they first tried 10 years ago at the BBC Proms.

BBC/Sisi Burn

BBC/Sisi BurnConversations with friends

The interactions in Beethoven’s conversation books, performed by Rhiannon and Thomas in the first half, range from the composer arguing with his nephew Karl van Beethoven to reminders to find time for a haircut or a bath.

Rhiannon likens the conversation books to the notes app on her phone, which she uses for shopping lists or asking strangers for directions.

Ahead of her first performance at the BBC Proms, the actor explained that in exploring the mundanities of the composer’s life and likening them to her own, he becomes less intimidating as a figure.

“What the conversations bring to life is he was just a man, doing his life, going to restaurants, being angry,” she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLaura Tunbridge, a musicologist and professor at the University of Oxford, explains by the 1820s Beethoven’s hearing had significantly deteriorated. He also suffered from gastrointestinal problems and had gone through a long legal case with his sister-in-law over the custody of Karl, who many of the remarks in the composer’s conversation books are attributed to.

“I think one of the interesting things is how we try and understand what it must be like to be a musician who has lost their hearing,” Laura says.

Nicholas Collon, conductor of the Aurora Orchestra, says the BSL exploration of Beethoven’s conversation books help shed light on this.

“In the last decades of his life, he couldn’t hear, he had lots of other medical problems. It wasn’t easy, his life, and yet he still manages to write music which is aspiring to uplift humanity.”

However, Nicholas says Beethoven’s deafness is not often explored in detail. “There’s not many examples of times when we have had a deaf actor on the stage talking about her deafness and how it corresponds to what Beethoven’s deafness was – I think that’s really important.

“It is extraordinary what he did in terms of his capacity for composition whilst deaf.”

Beethoven by heart

The second half of the performance is played by the Aurora Orchestra from memory, with the BBC Singers and National Youth Choir of Great Britain joining for a choral finale.

Nicholas says playing from memory helps create space to explore the social and cultural context of a piece of work.

“If you have to learn something from memory, you have a different concept of space and time,” Nicholas explains.

“Because the players are performing from memory, we can move them quite easily around the stage so that they can demonstrate bits of music,” he adds.

This, Nicholas says, helps guide an audience through the Ninth Symphony because “this is the biggest he ever wrote. It’s a mammoth piece.”

BBC/Sisi Burn

BBC/Sisi BurnRhiannon adds it has been helpful for her performance to work alongside the orchestra, who stand and physically respond to the music as it plays.

With the orchestra unobstructed by sheet music, the actor explains “it feels really connected on stage.”

“I could see and feel them breathing in,” Rhiannon says, which works as a “great cue” for her part in the piece.

Laura explains with his Ninth Symphony Beethoven was “really pushing the boundaries of what expectations were of the symphony.”

This, she says, was brought to life by the Aurora Orchestra’s performance.

“It is about what you hear, but it’s also very much about what you see and what you feel – be that vibration, the kind of physical experience of it, but also all of the gestures and eye contact.”