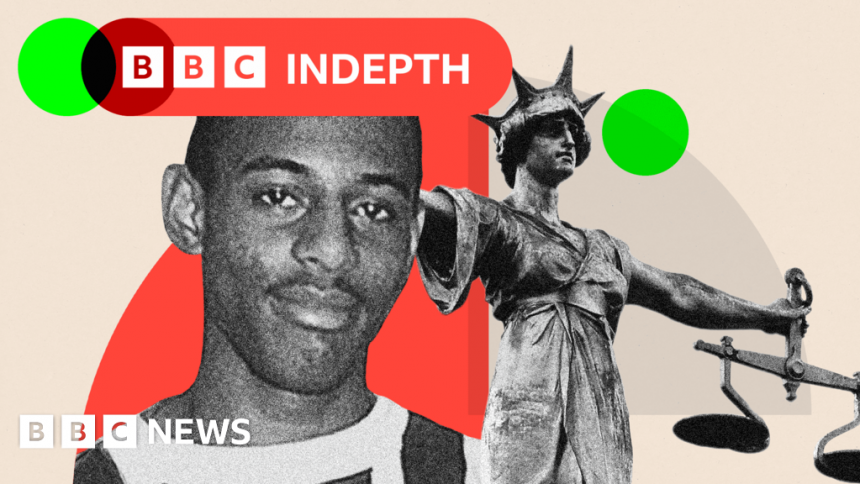

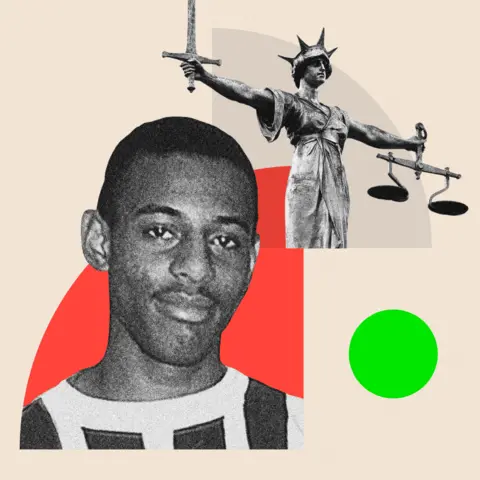

Stephen Lawrence would have been 50 today. Is there still a chance to get justice for him?

BBC

BBCStephen Lawrence would have turned 50 today.

His racist murder in 1993, when he was aged only 18, stole his life.

Amid the Metropolitan Police’s many failures, Stephen’s murder has never been fully solved and the 31 years since have been stolen, too, from his family, whose campaign for justice has been unceasing.

Stephen was stabbed to death by a gang of five or six young white men. He had been with his friend Duwayne Brooks waiting for a bus in Eltham, south London.

Only two of his killers have been convicted of murder, after a trial that concluded in 2012, meaning others responsible remain free. Another suspect has died.

Stephen’s case is the Met’s best-known and most controversial murder. It generated one of the great justice campaigns in UK history and has changed policing, the law, and society. The Met knows the case matters to millions of people and it is a case I have spent a large amount of time investigating for the BBC.

In 2020, the Met announced it was closing the murder investigation and that it had exhausted all viable lines of inquiry.

Following this, I began investigating and, last year, the BBC publicly identified a major suspect for the first time and exposed decades of Met failures relating to him.

For a long time, the suggestion that Stephen’s murder could ever be fully solved has seemed fanciful to many.

But if you look closely, as I have done, there may, in fact, be a genuine opportunity for further charges.

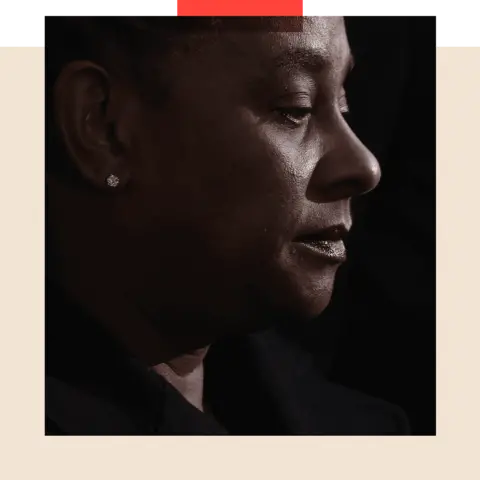

The current situation is that in April this year, following a series of further BBC revelations and calls by Stephen’s mother, Baroness Doreen Lawrence, for the case to be reopened, the Met was forced by the Mayor of London Sadiq Khan to announce an independent review of the murder would take place.

The mayor said the Lawrence family must be satisfied with the review.

This review, as proposed, means there is the potential for the case to be reopened should fresh or neglected lines of inquiry be identified.

Since then: stasis, despite a series of behind-the-scenes meetings and negotiations.

The process is now nearing a conclusion and can really only end in one of two ways: with the setting-up of a review that the Lawrence family supports; or with one they do not support and which therefore may not take place at all.

The review has been described as perhaps the last chance for justice by Imran Khan, the solicitor for Baroness Lawrence.

An independent police force or body capable of taking on a review has not been agreed. Some forces were considered but deemed unsuitable.

However, disagreements around the breadth and scope of the review have been the major stumbling block.

No limits

The Met has proposed that it should have a relatively narrow focus, looking at recent decision-making, mainly relating to the closure of the case in 2020 and how the force responded to my own investigation last year. This review would essentially be paper-based.

Stephen’s family want a far broader review, with no limits on what can be examined – meaning much earlier decisions and investigations stretching back to 1993 would be in scope.

The family think the Met may have neglected chances to bring the other killers to justice, something that can only be examined by a broad review with the power to make enquiries and speak to witnesses. The family are not asking for a full re-investigation of the whole case, but want a review that may lead to the case being formally reopened.

To understand why this issue is so crucial, we need to consider both the history of the case and the recent revelations.

The sheer number of investigations, inquiries, and other official processes spanning 31 years mean the case now, arguably, is uniquely complex, despite starting as one that should have been relatively straightforward to solve.

This complexity is now being held up by the Met as a reason why it is impractical to carry out a full review or reinvestigation – but of course the Met’s own failure to deliver full justice is central to this complexity.

The Met itself now accepts the first investigation in 1993 and 1994 was a failure. That investigation was lambasted in 1999 by the landmark Macpherson Report as having been “marred by a combination of professional incompetence, institutional racism and a failure of leadership”.

Given this, the Met had, and has, no choice but to accept it was a disaster.

But 1999 is now a long time ago. The Met has been defensive of its other investigations into the murder since that year, but then there hasn’t been another public inquiry examining its actions and producing official adverse findings after that point.

The Met, bluntly, has seemed content to lay the blame for everything that has gone wrong with the case on the first investigation. When I have asked the force if it accepts failings by later investigations, it has not done so, despite clear evidence of failures in reviews that took place after the publication of the Macpherson report.

In terms of the first investigation, failures are still being uncovered and new opportunities for evidence are being identified.

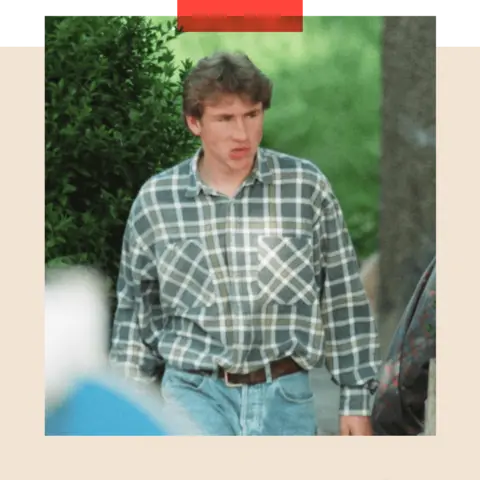

The suspect we named last year, Matthew White, was treated as a witness by the first investigation and was repeatedly referred to as such under an alias during Macpherson. But he was really a major suspect and the failure to identify him as one is arguably the worst of all those committed by the first investigating team.

Lord Sentamu, who was part of the Macpherson Inquiry team, has told me the murder would have been resolved in the 1990s if White had been dealt with properly and that Sir William Macpherson, who is now dead, would have felt he had failed by not having identified the White issue during his inquiry.

The fact that White’s stepfather had tried to tell the first investigation that White had admitted to being present during the murder was only uncovered in 2013 by Clive Driscoll, the officer who achieved the only two murder convictions in the case.

He uncovered all this after reviewing notes and messages from the first investigation and then going out to speak to people on the ground, which is what Stephen’s family now want from the new review.

Mr Driscoll was in the process of investigating White when he was made to retire early the next year and, from my own research, it is clear the Met did not subsequently fully pursue the lines of inquiry he was following, something the Met disputes. The Met has said it twice passed files on White to the Crown Prosecution Service. They ruled out murder charges, but my research has shown not everything possible was done prior to those files being submitted.

When investigating the case, which has meant knocking on doors all over the country, I repeatedly found that evidence from the first investigation could not be taken at face value, and that probing and testing it could generate opportunities and fresh leads.

Some witnesses have not been spoken to for many years, meaning the Met is not taking advantage of the fact that some people may now feel able to speak about what they know.

It is a maxim of police appeals that, over time, allegiances can shift and minds can change. But time is not a friend – witnesses are getting old, and some have died even during the time I’ve been investigating the case.

The Met’s focusing of the blame on what happened in 1993 and 1994, deflects from a critical examination of the various later investigations. These contained their own failures and therefore now hold their own opportunities as sources of evidence.

After the Macpherson report was published in 1999, a major investigation codenamed Operation Athena Tower took place. It was vast and costly, and employed techniques typically associated with counter-terrorism, including surveillance and bugging.

The Met have refused to acknowledge failures in Athena Tower, as it has about the investigation which preceded the closure decision in 2020. Neither resulted in any charges being brought. Indeed, the only successful Met investigation was the one run by Clive Driscoll between 2006 and 2014.

Mr Driscoll, whom I got to know well during my own research, had repaired relations between the Met and the Lawrences, which subsequently collapsed again after he left the Met. The family view him as honest and determined to get to the bottom of the case, regardless of whether that highlights failures in the Met’s other inquiries.

A sense of humiliation

This is why both of Stephen’s parents have separately proposed that Mr Driscoll must have a role in the new review, and that has been accepted by the Met. But he has made it clear he will only take part in a review if its terms of reference are acceptable to the family.

The context for all this is that, for some within the Met, there is a sense of humiliation about what’s been revealed about White since last year. Looking at the case with him as a suspect upends parts of the previously publicly accepted timeline of the night of the murder. Crucially, it further implicates the outstanding suspects and opens up evidential opportunities.

Given what we now know about what was missing from the investigation into White prior to his death, Stephen’s family now questions what has not been done in relation to the outstanding living suspects – namely Luke Knight and brothers Neil and Jamie Acourt. They have always denied murder.

There is now less fear in Eltham of the Acourts and the gangster father of David Norris, who was convicted of the murder in 2012. When I turned up to question the Acourts separately last year, they both fled and appeared very nervous.

The Met said it would not comment on this article, but – in response to previous stories – the force has said it reiterates apologies about the mistakes made in the initial investigation.

In July they said: “Earlier this year, we made the decision that we would seek an independent review of our recent approach to the murder of Stephen Lawrence, including material published by the BBC.

“The terms of reference for the review are currently being discussed with Baroness Lawrence, Dr Lawrence and Duwayne Brooks.”

There are leads that can still be pursued, which, should they go somewhere, could make a difference to the case. This information is also available within the Met and would be considered by the type of broad review proposed by Stephen’s family.

There is some forensic evidence relating to a suspect. I know which suspect, but the BBC is not naming him. He does not know himself and could yet face further investigation.

Contrary to the organisation’s defensive public statements, a Met source has told me that, at senior levels within the Met, the force accepts various leads were left unfollowed when the investigation closed in 2020. But according to the source, the same senior members of the force do not feel under enough public pressure to reopen the case.

My understanding is that the prevailing decision to keep the case closed is therefore not based on a cool balancing of all the evidence after every possible line of inquiry has been exhausted. It is a matter of will.

Just as Stephen would now have been entering his 50s, the mother and father who have never stopped fighting for him are into their 70s and 80s, respectively.

With unsolved murders, there can sometimes be a passive sense that, in time, we will somehow eventually find out what really happened. But, based on what I have found out about this case, uncovering what happened will require active effort.

In the case of Stephen Lawrence, time itself will not reveal the truth.

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.