Boeing strike: ‘My $28-an-hour pay isn’t enough to get by’

BBC

BBCMore than 30,000 Boeing workers are on strike after their union rejected a deal that would have raised pay in exchange for the loss of bonuses and pensions.

The employees are now in their second week of striking with no sign of any deal with Boeing management on the horizon.

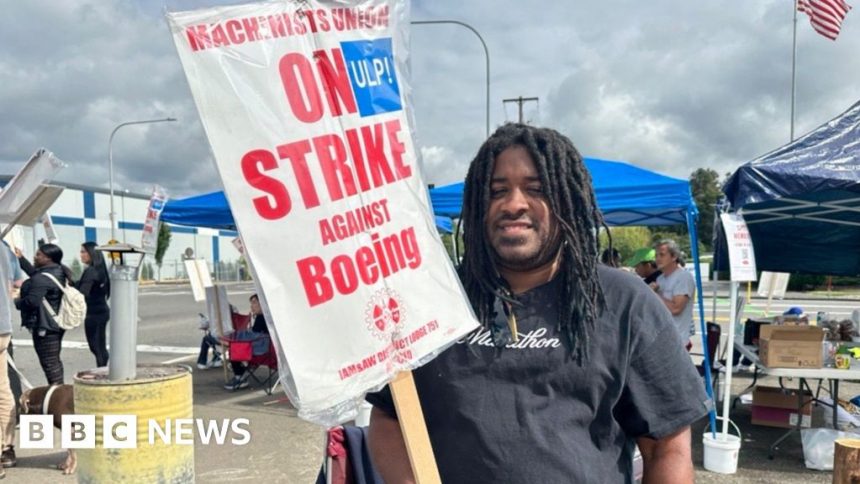

We asked workers on the picket line outside a Boeing factory in Auburn, Washington, why they feel they have no choice but to strike.

Many of the strikers the BBC spoke to cited the loss of their bonuses and pensions, as well as inflation and the cost of living, as their reasons for walking out.

Davon Smith, 37, earns under $28 (£21) an hour attaching the wings to Boeing 777X planes, which sell for over $400m (£300m) each. He also works as a security guard at a bar to make ends meet.

“That kind of keeps me afloat, a little bit,” he says about the part-time security job.

His fiancée, who works as a secretary for Seattle schools, earns more than him.

Smith, who has worked at Boeing for only a year, says his pay rate doesn’t compensate him for the level of safety that goes into ensuring that the planes don’t fail.

He says he’s concerned he could be held criminally liable if his work isn’t done correctly.

“Every time we make a plane to their spec, we pretty much put our life on the line. Because if anything goes wrong – like if it’s a torque’s out of spec or something like that – and potentially the plane goes down, we obviously get [jail] time for that,” he says.

The deal that union representatives and Boeing had tentatively agreed would have seen workers get a 25% pay rise over four years.

It also offered improved healthcare and retirement benefits, 12 weeks of paid parental leave, and would have given union members more say on safety and quality issues.

However, the union had initially targeted a 40% pay rise, and almost 95% of union members who voted rejected the deal.

Many remain angry about benefits lost during contract negotiations years ago – especially the pension, which guaranteed certain payouts in retirement.

Now, the firm contributes to worker investment accounts known as 401(k)s, making their values subject to the strength of the stock market.

“They just took everything away. They took away our pensions, they took away our bonuses that people rely on,” says Mari Baker, 61, who started at Boeing in 1996 and currently works as a kitter, overseeing the tools used at factories.

She calls the rejected deal “a slap in the face”, but says she is worried about losing her health insurance at the end of the month, if the strike continues and whether she’ll be able to afford her prescription medication.

Boeing declined to comment for this story, pointing to earlier comments by executives pledging to reset the relationship with workers and work towards a deal as soon as possible.

Before the stoppage, the company was already facing deepening financial losses and struggling to repair its reputation after a series of safety issues.

New chief executive Kelly Ortberg, who was appointed to turn the business around, had urged workers not to strike as it would put the company’s “recovery in jeopardy”.

On Wednesday, the firm announced it was suspending the jobs of tens of thousands of staff in the US as a way of saving money in response to the strike.

Patrick Anderson, chief executive of the Anderson Economic Group, a research and consulting firm, says Boeing is a company “on the precipice”.

His firm estimates that the strike, just in its first week, has already cost workers at the firm and its suppliers more than $100m in lost wages and shareholders more than $440m, among other economic losses.

“This strike doesn’t just threaten earnings, it threatens the reputation of the company at a time when that reputation has suffered hugely,” he says.

Workers on the picket line dismiss the threat to the firm, saying they have little to lose.

“This past year working here I couldn’t afford to pay my mortgage,” says Kerri Foster, 47, who joined Boeing last year after leaving her previous career as a nurse and now works as an aerospace mechanic.

Foster says that she has not been “making enough to pay basic bills”. Meanwhile, the cost of living is increasing, along with her mortgage payments and property taxes.

She’s willing to keep striking until her pay is increased and pension restored, despite the loss of income while the strike continues.

“I’m hungry already. I mean, if you can’t pay your bills when you’re going to work, what’s the difference?” she says.

Ryan Roberson, 38, works in the final assembly division at Boeing. He brought two of his six children to the picket line with him on Wednesday.

As an employee at Boeing for less than a year, the plan that the union rejected would not have had any impact on his wages. Increases would have only gone to those working for more than a year.

He says he plans to keep striking until workers at “that entry level can have a liveable wage”.

The International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers union, which represents the strikers, has issued debit cards to members.

After the strike goes into its third week, workers will receive $250 each week, which will be deposited on to the card.

That $250 “will buy a lot of Top Ramen”, says Roberson, referring to the ultra-cheap instant noodles.

Marc Cisneros, 29, says he is striking “because for the amount of work I do and the quality that I produce, it seems unfair that I’m unable to afford my rent”.

He says Boeing is “putting me in essential poverty even though I’m working 40, 50, 60 hours per week”.

Cisneros has worked at Boeing for four years. His girlfriend works there as well. His mother also worked there, “making a decent amount of money” which supported him and his sibling.

He says he’s proud to work at Boeing and is disappointed by his lack of compensation from a company he hopes to work for until he retires.

“I mean this is dangerous. It’s big hunks of metal flying through the sky,” he says.

“You gotta take pride in the quality [and] in everything that you do here. Our names are on every single thing that we produce.”