What I found on the secretive tropical island they don’t want you to see

BBC

BBCDiego Garcia, a remote island in the Indian Ocean, is a paradise of lush vegetation and white-sand beaches, surrounded by crystal blue waters.

But this is no tourist destination. It is strictly out of bounds to most civilians – the site of a highly secretive UK-US military base shrouded for decades in rumour and mystery.

The island, which is administered from London, is at the centre of a long-running territorial dispute between the UK and Mauritius, and negotiations have ramped up in recent weeks.

The BBC gained unprecedented access to the island earlier this month.

___

“It’s the enemy,” a private security officer jokes as I return to my room one night on Diego Garcia, my name highlighted in yellow on a list he is holding.

For months, the BBC had fought for access to the island – the largest of the Chagos Archipelago.

We wanted to cover a historic court case being held over the treatment of Sri Lankan Tamils, the first people ever to file asylum claims on the island, who have been stranded there for three years. Complex legal battles have been waged over their fate and a judgement will soon determine if they have been unlawfully detained.

Up until this point, we could only cover the story remotely.

Diego Garcia, which is about 1,000 miles (1,600 km) from the nearest landmass, features on lists of the world’s most remote islands. There are no commercial flights and getting there by sea is no easier – permits for boats are only granted for the archipelago’s outer islands and to allow safe passage through the Indian Ocean.

To enter the island you need a permit, only granted to people with connections to the military facility or the British authority that runs the territory. Journalists have historically been barred.

UK government lawyers brought a legal challenge to try to block the BBC from attending the hearing, and even when permission was granted following a ruling by the territory’s Supreme Court, the US later objected, saying it would not provide food, transport or accommodation to all those attempting to reach the island for the case – including the judge and barristers.

Notes exchanged between the two governments this summer, seen by the BBC, suggested both were extremely concerned about admitting any media to Diego Garcia.

“As discussed previously, the United States agrees with the position of HMG [His Majesty’s Government] that it would be preferable for members of the press to observe the hearing virtually from London, to minimize risks to security of the Facility,” one note sent from the US government to British officials said.

When permission was finally granted for me to spend five days on the island, it came with stringent restrictions. These did not just cover the court reporting. They also extended to my movements on the island and even a ban on reporting what the actual restrictions were.

Requests for minor changes to the permit were denied by British and US officials.

Personnel from the security company G4S were flown to the territory to guard the BBC and lawyers who had flown out for the hearing.

But despite the constraints, I was still able to observe illuminating details, all of which helped to paint a picture of one of the most restricted locations in the world.

Approaching by plane, coconut trees and thick foliage are visible across the 44 sq km footprint-shaped atoll, the greenery punctuated by white military structures.

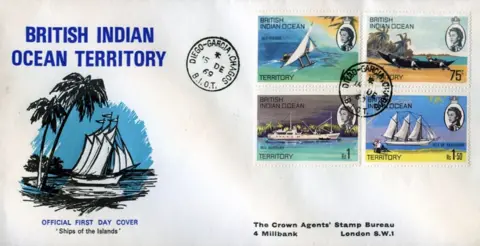

Diego Garcia is one of about 60 islands that make up the Chagos Archipelago or British Indian Ocean Territory (Biot) – the last colony established by the UK by separating it from Mauritius in 1965. It is located about halfway between East Africa and Indonesia.

Pulling on to the runway alongside grey military aircraft, a sign on a hangar greets you: “Diego Garcia. Footprint of Freedom,” above images of the US and British flags.

This is the first of many references to freedom on the island’s signage, a nod to the UK-US military base that has been there since the early 1970s.

Agreements signed in 1966 leased the island to the US for 50 years initially, with a possible extension for a further 20 years. The arrangement was rolled over and is set to expire in 2036.

US Navy

US NavyAs I make my way through airport security and beyond, US and UK influences jostle for predominance.

In the terminal, there is a door decorated with a union jack print and walls hung with photos of significant British figures, including Winston Churchill.

On the island itself, I spot British police cars and a nightclub called the Brit Club with a bulldog logo. We pass roads named Britannia Way and Churchill Road.

But cars drive on the right, as they do in the US. We are driven around in a bright yellow bus reminiscent of an American school bus.

The US dollar is the accepted currency and the electricity sockets are American. The food offered to us for the five days includes “tater tots” – a popular American fried-potato side dish – and American biscuits, similar to British scones.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the territory is administered from London, most personnel and resources there are under the control of the US.

In the BBC’s bid to access the island, UK officials referred questions up to US staff. When the US blocked the court hearing from taking place on Diego Garcia this summer, a senior official at the Ministry of Defence said the UK “did not have the ability to grant access”.

“The US security assessment is classified… [they] have demonstrated that they have strict controls in place,” he wrote in an email to a Foreign Office colleague.

Biot’s acting commissioner has said it is not possible for him to “compel the US authorities” to grant access to any part of the military facility constructed by the US under the terms of the UK-US agreement, despite it being a British territory.

In recent years, the territory has been costing the UK tens of millions of pounds, with the bulk of this categorised under “migrant costs”. Communications obtained by the BBC between foreign office officials in July regarding the Sri Lankan Tamils warn that “the costs are increasing and the latest forecast is that these will be £50 million per annum”.

The atmosphere on the island feels relaxed. Troops and contractors ride past me on bikes, and I see people playing tennis and windsurfing in the late afternoon sun.

A cinema advertises screenings of Alien and Borderlands, and there is even a bowling alley and a museum with a gift shop attached, though I was not allowed inside.

We pass a fast-food spot called Jake’s Place, and a scenic patch of land next to the sea with a sign that reads: “Ye olde swimming hole and picnic area.” Diego Garcia-branded T-shirts and mugs are on sale on the island.

But there are also constant reminders of the sensitive base that is here. Military drills can be heard early in the morning, and near our accommodation block is a fenced-off building identified as an armoury.

All the time, US and British military officials keep a close eye on the court’s movements.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe island has startling natural beauty, from lush vegetation to pristine white beaches, and is also home to the world’s biggest terrestrial arthropod – the coconut crab. Military personnel warn of the dangers of sharks in the surrounding waters.

Biot’s website boasts that it has the “greatest marine biodiversity in the UK and its Overseas Territories, as well as some of the cleanest seas and healthiest reef systems in the world”.

But there are also clues pointing to its brutal past.

When the UK took control of the Chagos Islands – Diego Garcia is the southernmost – from former British colony Mauritius, it sought to rapidly evict its population of more than 1,000 people to make way for the military base.

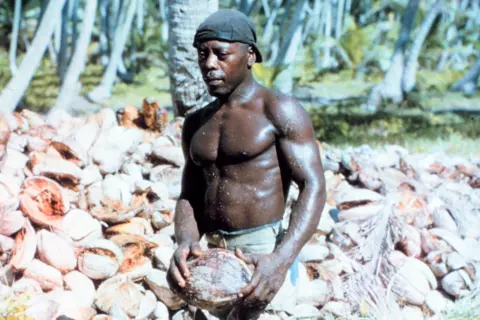

Enslaved people were brought to the Chagos Islands from Madagascar and Mozambique to work on coconut plantations under French and British rule. In the following centuries, they developed their own language, music and culture.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesI get to see a former plantation on the east of the island, where buildings stand in disrepair. The grand plantation manager’s house has a sign outside reading: “Danger unsafe structure. Do not enter. By order: Brit rep [representative].” A large crab crawls up the door of an abandoned guest house.

At a church on the plantation site, a sign, in French, beneath the crucifix reads: “Let us pray for our Chagossian brothers and sisters.”

Wild donkeys still roam in the area. David Vine, author of Island of Shame: The Secret History of the US Military Base on Diego Garcia, describes them as a “ghostly remnant of the society that had been there for almost 200 years”.

A Foreign Office memo in 1966 stated that the object of its plan “was to get some rocks which will remain ours; there will be no indigenous population except seagulls”.

A British diplomat responded that the islands were home only to “some few Tarzans or Man Fridays whose origins are obscure and are hopefully being wished on to Mauritius”.

Another government document stated that the islands were chosen “not only for their strategic location but also because they had, for all practical purposes, no permanent population”.

“The Americans in particular attached great importance to this freedom of manoeuvre, divorced from the normal considerations applying to a populated dependent territory,” it said.

Mr Vine says the plans came at a time when the “decolonisation movement was unfolding and accelerating” and the US was concerned about losing access to military bases around the world.

Diego Garcia was one of many islands that were considered, he says, but it became the “prime candidate” because of its relatively small population and strategic location in the middle of the Indian Ocean.

For the UK, he says, it was a chance to maintain close military ties with the US, even with only a “token British presence” there – but there was also financial motivation, he adds.

The US agreed to a $14m discount on the UK’s purchase of its Polaris nuclear missiles as part of the secret deal over the islands.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn 1967, the eviction of all residents from the Chagos islands began. Dogs, including pets, were rounded up and killed. Chagossians have described being herded onto cargo ships and taken to Mauritius or the Seychelles.

The UK granted citizenship to some Chagossians in 2002, and many of them came to live in the UK.

In testimony given to the International Court of Justice years later, Chagossian Liseby Elysé said people on the archipelago had lived a “happy life” that “did not lack anything” before the expulsions.

“One day the administrator told us that we had to leave our island, leave our houses and go away. All persons were unhappy. But we had no choice. They did not give us any reason,” she said. “Nobody would like to be uprooted from the island where he was born, to be uprooted like animals.”

Chagossians have fought for years to return to the land.

Mauritius, which won independence from the UK in 1968, maintains that the islands are its own and the United Nations’ highest court has ruled, in an advisory opinion, that the UK’s administration of the territory is “unlawful” and must end.

It said the Chagos Islands should be handed over to Mauritius in order to complete the UK’s “decolonisation”.

Clive Baldwin, senior legal adviser at Human Rights Watch, says the “forced displacement of the Chagossians by the UK and US, their persecution on the grounds of race, and the ongoing prevention of their return to their homeland amount to crimes against humanity”.

“These are the most serious crimes a state can be responsible for. It is an ongoing, colonial crime as long as they prevent the Chagossians from returning home.”

The UK government has previously stated that it has “no doubt” as to its claim over the islands, which had been “under continuous British sovereignty since 1814”.

However, in 2022, it agreed to open negotiations with Mauritius over the future of the territory, with then-Foreign Secretary James Cleverly saying he wanted to “resolve all outstanding issues”.

Earlier this month, the government announced that former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s chief of staff, Jonathan Powell, who played a central role in negotiating the Good Friday agreement in Northern Ireland, had been appointed to negotiate with Mauritius over the islands.

In a statement, new Foreign Secretary David Lammy – who has criticised previous governments for having for years “ignored the opinions” of various UN bodies over the islands – said the UK was endeavouring to “reach a settlement that protects UK interests and those of our partners”, as he stressed the need to protect the “long-term, secure and effective operation of the joint UK/US military base”.

Matthew Savill, military sciences director at leading UK defence think tank Rusi, says Diego Garcia is an “enormously important” base, “because of its position in the Indian Ocean and the facilities it has: port, storage and airfield”.

The nearest UK facility is some 3,400km (2,100 miles) away, and for the US, nearly 4,800km (3,000 miles), he explains, with the island also an important location for “space tracking and observation capabilities”.

Tankers operating from Diego Garcia refuelled US B-2 bombers that had flown from the US to carry out the first airstrikes on Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks. And, during the subsequent “war on terror”, aircraft were also sent directly from the island itself to Afghanistan and Iraq.

Alamy

AlamyThe base is also one of an “extremely limited number of places worldwide available to reload submarines” with weapons like Tomahawk missiles, says Mr Savill, and the US has positioned a large amount of equipment and stores there for contingencies.

Walter Ladwig III, a senior lecturer in international relations at King’s College London, agrees the base fulfils “a lot of important roles” – but that “there is this level of secrecy that seems to go beyond what we see at other places”.

“There has been this hyper-focus on controlling access and on limiting access, which… seems to go beyond what, given what we publicly know about the assets, capabilities and units are based there.”

During my time on the island, I am required to wear a red visitor pass and am closely monitored at all times. My accommodation is guarded 24-hours-a-day and the men outside make a note of when I leave and return – always under escort.

In the mid-1980s, British journalist Simon Winchester pretended his boat had run into trouble next to the island. He remained in the bay for about two days, and managed to briefly step on shore before being escorted away and told: “Go away and don’t come back.”

He tells me he remembers British authorities there being “incredibly hostile” and the island as “extraordinarily beautiful”. More than two decades later, a Time magazine journalist spent 90 minutes or so on the island when the US presidential plane stopped there to refuel.

Rumours have long swirled about the uses of Diego Garcia, including that it has been used as a CIA black-site – a facility used to house and interrogate terror suspects.

The UK government confirmed in 2008 that rendition flights carrying terror suspects had landed on the island in 2002, following years of assurances that they had not.

“The detainees did not leave the plane, and the US Government has assured us that no US detainees have ever been held on Diego Garcia. US investigations show no record of any other rendition through Diego Garcia or any other Overseas Territory or through the UK itself since then,” then-Foreign Secretary David Miliband told parliament at the time.

On the same day, former CIA director Michael Hayden said that information previously “supplied in good faith” to the UK about rendition flights – stating that they had never landed there – had “turned out to be wrong”.

“Neither of those individuals was ever part of [the] CIA’s high-value terrorist interrogation programme. One was ultimately transferred to Guantanamo, and the other was returned to his home country. These were rendition operations, nothing more,” he said, while denying reports that the CIA had a holding facility on Diego Garcia.

Years later, Lawrence Wilkerson, chief of staff to the former US Secretary of State Colin Powell, told Vice News that intelligence sources had told him that Diego Garcia had been used as a site “where people were temporarily housed and interrogated from time to time.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesI was not allowed near any of Diego Garcia’s sensitive military areas.

After leaving my island accommodation for the last time I received an email, thanking me for my recent stay and asking for feedback. “We want every guest to experience nothing less than a welcoming and comfortable experience,” it read.

Before flying out, my passport was stamped with the territory’s coat of arms. Its motto reads: “In tutela nostra Limuria”, meaning “Limuria is in our charge” – a reference to a mythical lost continent in the Indian Ocean.

A continent that doesn’t exist seems like a fitting symbol for an island whose legal status is in doubt and that few, since the Chagossians were expelled, have been allowed to see.