Artist inspired by council estate childhood wants to make art more inclusive

@gethintjones

@gethintjonesArtist Natalie Chapman grew up feeling stigmatised that she lived in a council house, received free school meals and had a parent in and out of rehab.

“You face prejudice from people, people have ideas about people who live in in council houses,” she said.

In her most personal project to date, she has turned her childhood memories into a collection of bold, autobiographical portrait paintings called All The Stories I Could Never Tell.

“I don’t want my exhibition to be like poverty porn, because it’s not,” she said. “There’s a lot of love within those paintings and there’s a lot of support.”

@gethintjones

@gethintjonesNatalie, 43, grew up mostly on the mid Wales coast in Ceredigion, with “very, very loving” parents but money was scarce, her attendance at school was sporadic, and her late father’s drug addiction meant time in rehab.

Before getting social housing in the early 1980s the family lived in a home with no electricity, using paraffin lamps for light.

Later the large family bought a one-bedroom cottage where they all lived in one room before it was repossessed.

“When I was really little I remember friends being like, ‘my mum says that we’re not allowed to play with you because you’re a hippie and you can’t come round to our house’,” she said.

As a young teenager Natalie took part in a France exchange programme, but on her return home the French student wrote to her suggesting she was not going to be staying with her family when she came to Wales.

Natalie decided to ask a teacher about it.

“She sort of just blurted it out in front of everybody, ‘we’ve decided your family’s not suitable, so she won’t be coming stay with you’,” recalled Natalie.

Instead the student stayed with a child from a “well-to-do family”, she said.

“It relayed back to me ‘I’m not deserving of this chance’ and I think there’s so many situations and scenarios that actually still exist, a lot of those things haven’t changed.”

@gethintjones

@gethintjonesNatalie said only recently she saw another example of this kind of attitude towards people who live in social housing.

A family member posted on social media that she was looking for someone to swap council houses with her as she was looking for more space. She then received a barrage of negative responses.

“It was like, ‘you’ve got a council house, you should be grateful’,” said Natalie.

“It’s almost like you’re not allowed to want to better yourself and things are built to keep you there.”

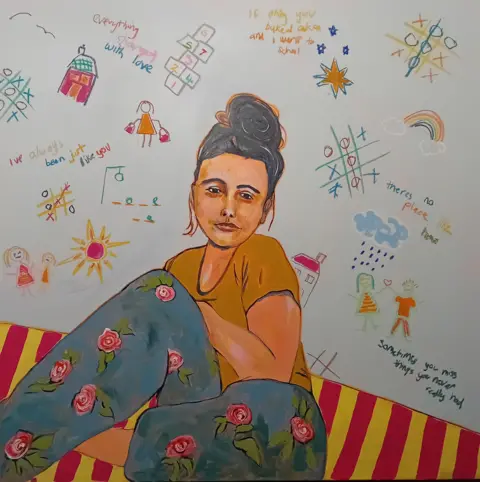

One of her paintings is called ‘If only you baked cakes and I went to school’ and depicts a young Natalie in her childhood bedroom.

“I remember wanting those things when I was that age,” said Natalie.

“I remember thinking, ‘God, why isn’t my mum wearing an apron and making scones?,” she laughed.

“The pressure of the outside world was seeping in… but she didn’t make scones because we didn’t have money to do baking and I didn’t go to school because I didn’t feel nurtured there and I didn’t feel that there was a proper space for me there.”

@gethintjones

@gethintjonesAnother of her paintings is called ‘Club Tropicana Dreams’ and is “kind of about mine and my mum’s relationship” and also is a reference to Club Tropicana, the hit by 1980s pop superstars Wham!.

“Dreams are important and if you lose your dreams you’re lost,” she said.

“When you’re having to think about where your next meal is coming from, how you’re going to survive next week until your next payment comes through, can you afford to run a car… you forget what you wanted your life to be or what you wanted it to feel like.”

Natalie said she was able to experience art as a child because of a man called Chris Robertson, who had a bus and would pick up her and other children living in difficult circumstances and take them to arts activities.

At 16 she left school with few GCSEs. She worked in a care home and a pub until she was 19, then got three A-levels at a further education college before having her four children, now aged 22, 17, 14, and six.

It was not until she was in her 30s that she went to University of Wales Trinity Saint David, where she gained a degree in fine art.

At the time she was a single parent with three children under the age of six.

“My friend who was living in a council house on the opposite side of the estate to me was like, ‘I’ll look after the kids for you’,” she said.

Her painting Sink or Swim depicts her and that best friend, who made getting her degree possible.

Andrew Chittock

Andrew ChittockToday Natalie makes her living selling her art online, teaching and framing out of Gallery Gwyn in Aberaeron.

Her current show, which is at Canfas Art Gallery in Cardigan in Ceredigion until 30 November, is her ninth solo exhibition.

She said her career had been forged through “absolute perseverance”.

Using her living room as a studio, she creates her paintings using old photos which “get reimagined” using charcoal and acrylic and occasionally mixed media such as spray paint and pastels.

“My work is autobiographical because I don’t really know how not to be,” she said.

“But there’s that child that’s still in me that’s like, ‘oh, don’t tell anybody the truth because they’ll think you’re this or that’ – that doesn’t ever really leave you,” she said.

She hopes people recognise themselves in her art and wants it to spark conversation.

She is on a mission to “make the art world more inclusive and approachable” and works for a charity offering free art and music classes to 11-19-year-olds.

One way to achieve this, she believes, is ensuring all schools offer children the opportunity to study creative subjects at school, such as music, textiles and drama.

“The arts have become expensive hobbies for the rich when it should be accessible to all,” she said.

She also wants to see more galleries taking a risk on the art they show.

“There’s a lot of deprivation in Wales, there’s lots of stories that aren’t being told on gallery walls,” she said.

“Who better to have interesting stories about their lives than people who’ve gone through things – to me the most interesting thing is people who face challenges and come through them, that’s where the richness of life is.”