Tenants may not be able to buy new council homes – Rayner

PA Media

PA MediaThe deputy prime minister has suggested she wants to stop new council homes in England from being sold under the Right to Buy scheme.

Angela Rayner told the BBC the government would put restrictions on new social homes in England “so that we aren’t losing that stock”.

For decades, the Right to Buy scheme has allowed social housing tenants to buy their homes, often at a significant discount.

Ms Rayner said the country was facing a “homelessness crisis”, as she announced £10m to help rough sleepers get through the winter.

Right to Buy was introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1980. Since then, more than two million homes have been sold.

The policy was initially credited with increasing rates of home ownership, but more recently has been blamed for contributing to the rise in homelessness.

Labour has pledged to build the largest number of social and council homes since World War Two. Ms Rayner told the BBC that she doesn’t want those newly built properties “leaving the system”.

“We’ll be putting restrictions on them so that we aren’t losing those homes… we’re not losing that stock.”

Ministers will launch a consultation on the issue later this year.

Right to Buy was relaunched in 2012 by the Conservative-led coalition government, which increased the discount a tenant could receive when buying their home.

It currently stands at £102,400 across England except in London where it is £136,400.

Since coming to office, Labour has said the discount will be reduced to between £16,000 and £38,000, depending on location. Last month’s Budget also saw measures allowing local authorities to keep all the money they receive from council house sales, a policy the last Conservative government also followed for two years until March 2024.

Previously, they had to give a proportion of each sale to the Treasury.

Right to Buy was ended in Scotland in 2016, and in 2019 the Welsh government stopped the policy.

Angela Rayner said England was facing a “catastrophic emergency situation” in relation to homelessness.

Visiting a hostel for rough sleepers in south London, she met some of those who have recently been helped off the streets. The latest data shows that 4,780 people were seen sleeping outside in the city in the three months between June and September of this year, a record high.

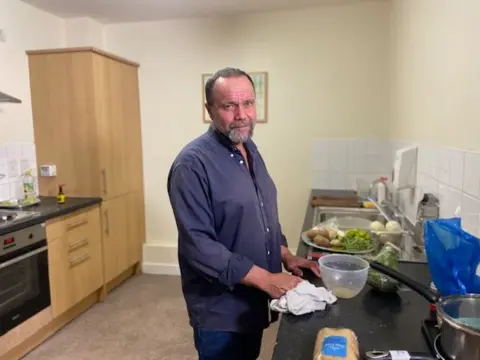

Stephen Richards, 58, spent several weeks sleeping in gardens and woods before recently coming to the centre. An experienced chef, he said a breakdown in family relations had cost him his home, and the cost of renting had prevented him from securing another property.

“Years ago, a room in somebody’s house was called a lodger,” he said.

“Now they’re calling them en-suite [rooms]. They’re charging £1,200 for a bedroom a month. Things are too expensive.”

The deputy PM highlighted the £233m committed in the Budget to tackle all forms of homelessness, bringing the total to almost £1bn in 2025-26.

The government has now also pledged £10m to tackle rough sleeping, which it says will go directly to councils in the highest need.

The number of households living in temporary accommodation is at record levels, including more than 150,000 children. Acknowledging the problem “won’t be fixed overnight”, Ms Rayner said tackling homelessness would need different government departments to work together.

A crucial step is to reduce the number of people who are becoming homeless in the first place.

Emma Haddad, chief executive of homeless charity St Mungo’s, said she was encouraged by the government’s determination to push through the Renters’ Rights Bill.

The bill will end Section 21 evictions in England, where landlords can ask tenants to leave without having to give a reason.

“We know that most people becoming homeless are coming out the private-related sector, and Section 21 evictions is a large driver [of that]. It’s going to help dramatically,” said Ms Haddad.