Democrats dreamt of an unbeatable coalition. Trump turned it to dust

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDonald Trump swept to victory on Tuesday by chipping away at groups of voters which Democrats once believed would help them win the White House for a generation.

After Barack Obama’s victory in 2008, many triumphantly claimed that the liberal voting coalition which had elected the first black president was growing more powerful, as the makeup of America changed.

Older, white conservatives were dying off, and non-white Americans were projected to be in the majority by 2044. College-educated professionals, younger people, blacks, Latinos and other ethnic minorities, and blue-collar workers were part of a “coalition of the ascendant”.

These voters were left-leaning on cultural issues and supportive of an active federal government and a strong social safety net. And they constituted a majority in enough states to ensure a Democratic lock on the Electoral College – and the presidency.

“Demography,” these left-wing optimists liked to say, “is destiny.” Sixteen years later, however, that destiny appears to have turned to dust.

Cracks began forming when non-college educated voters slipped away from the Democrats in midterm elections in 2010 and 2014. They then broke en masse to Trump in 2016. While Joe Biden, with his working-class-friendly reputation built over half a century, won enough back to take the White House in 2020, his success proved to be only a temporary reprieve.

This year, Trump supplemented his gains with the blue-collar workers by also cutting into the Democratic margins among young, Latino and black voters. He has carved up the coalition of the ascendant.

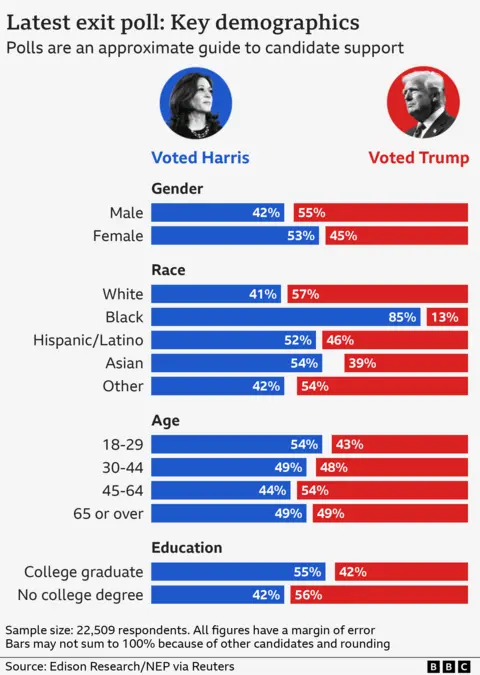

According to exit polls, Trump won:

– 13% of the black vote in 2024 compared to Republican John McCain’s 4% against Obama

– 46% of the Latino vote this time, while McCain got 31% in 2008

– 43% of voters under 30 against the 32% for McCain

– 56% of those without a college degree – back in 2008, it was Obama who won a majority

Speaking on Thursday after his comeback victory, Trump celebrated his own diverse coalition of voters.

“I started to see realignment could happen because the Democrats are not in line with the thinking of the country,” the president-elect told NBC News.

Immigration and identity politics

Trump did it with a hard-line message on immigration that included border enforcement and mass deportations – policies that Biden and the Democrats recoiled from when they took power back from Trump in 2021, lest they anger immigrant rights activists in their liberal base.

Illegal border crossings reached record levels under the Biden administration, with more than eight million encounters with migrants at the border with Mexico.

“If you watch a video from Hillary Clinton back in 2008 in the primaries, she talks about making sure there’s wall-building, making sure that that immigrants who violate the law get deported, making sure everybody learns English,” said Kevin Marino Cabrera, a Republican commissioner in Miami-Dade County. “It’s funny how far to the left [the Democrats] have gone.”

This week, Trump became the first Republican since 1988 to win that heavily Latino county in Florida. He also won Starr County in south Texas, with its 97% Latino population, with 57% of the vote. In 2008, only 15% of the county voted for McCain, the Republican.

Mike Madrid, an anti-Trump Republican strategist who specialises in Latino voting trends, told the BBC that the problem with “demography is destiny” was that it risked treating all non-white Americans as an “aggrieved racial minority”. “But that is not and nor has it ever been the way Latinos have viewed themselves,” he added.

“I hate that if you’re black, you’ve got to be a Democrat or you hate black people and you hate your community,” Kenard Holmes, a 20-year-old student in South Carolina, told the BBC during the presidential primaries earlier this year. He said he agreed with Republicans on some things and felt Democratic politicians took black voters for granted.

With some states still tabulating their results, Trump currently has improved on his electoral margins in at least 2,367 US counties, while slipping in just 240.

It wasn’t just the number of counties that Trump won that made a difference, either. Kamala Harris needed to post significant margins in the cities to offset Republican strength in rural areas. She consistently fell short.

In Detroit’s Wayne County, for example, which the latest US Census reports is 38% black, Harris won 63% of the vote – significantly lower than Joe Biden’s 68% in 2020 and Obama’s 74% in 2008.

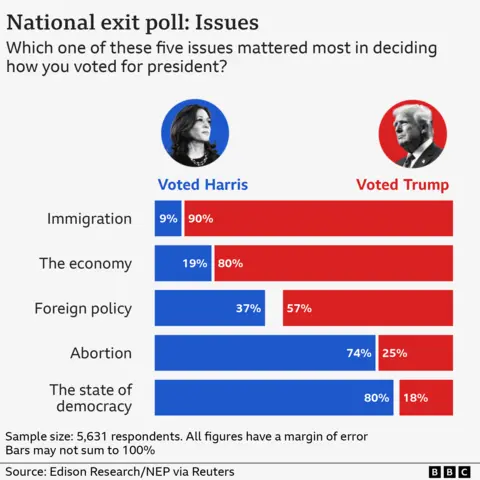

Polls consistently suggested that the economy, along with immigration, were the two issues of highest importance to voters – and where polls indicated Trump had an advantage over Harris.

His economic message cut across racial divides.

“We’re just sick of hearing about identity politics,” said Nicole Williams, a white bartender with a black husband and biracial children in Las Vegas, Nevada – one of the key battleground states that Trump flipped this year.

“We’re just American, and we just want what’s best for Americans,” she said.

The Democratic blame game begins

Democrats are already engaged in considerable soul-searching, as they come to grips with an election defeat that has delivered the White House, the Senate and, perhaps, the House of Representatives to Republican control.

Various elements within the party are offering their own, often conflicting, advice on the best path from the wilderness back to power.

Left-wing Senator Bernie Sanders, who twice ran for the Democratic presidential nomination, also criticised identity politics and accused the party of abandoning working-class voters.

Some centrist Democrats, meanwhile, have argued that the struggle to connect with voters goes beyond the economy and immigration. They point to how the Trump campaign was also able to use a cultural message as a wedge to fracture the Democratic coalition.

Among the positions that Republicans targeted in this year’s election were calls to shift funding away from law enforcement, decriminalise undocumented border-crossings and minor crimes like shoplifting, and provide greater protections for transgender Americans.

Many arose after the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the resulting rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, as well as other efforts to advance social justice and acknowledge darker parts of American history.

Within a few years, however, some of those positions proved a liability for Democrats when trying to win over persuadable voters and keep their coalition from fraying. Harris, for example, backed away from some positions she’d taken when she first ran for president in 2019.

In the last month of the presidential campaign, the Trump team made the vice-president’s past support for taxpayer-funded gender transition surgeries for federal prisoners and detained immigrants a central focus.

One advert ended with the line: “Kamala is for they/them. President Trump is for you.”

The Trump campaign spent more than $21m on transgender issue ads in the first half of October – about a third of their entire advertising expenditures and nearly double what they spent on spots on immigration and inflation, according to data compiled by AdImpact.

It’s the kind of investment a campaign makes if it has hard data showing an advert is moving public opinion.

After Trump’s convincing win, Congressman Seth Moulton, a moderate from Massachusetts, said his party needed to rethink its approach on cultural issues.

“Democrats spend way too much time trying not to offend anyone rather than being brutally honest about the challenges many Americans face,” Moulton told the New York Times. “I have two little girls, I don’t want them getting run over on a playing field by a male or formerly male athlete, but as a Democrat I’m supposed to be afraid to say that.”

Progressive Democrats, meanwhile, reject that characterisation, and argue that standing up for the rights of minorities has always been a core value of the party. Congressman John Moran wrote on X in response: “You should find another job if you want to use an election loss as an opportunity to pick on our most vulnerable.”

Mike Madrid, the political strategist, has a brutal assessment of where the Democratic coalition is today.

“The Democratic Party was predicated on what really is an unholy alliance between working-class people of colour and wealthier white progressives driven and animated by cultural issues,” Madrid said. “The only glue holding that coalition together was anti-Republicanism.”

Once that glue came unstuck, he said, the party was ripe for defeat.

Future elections are sure to be held in a friendlier political environment for Democrats. And Trump, who has shown a unique ability to attract new and low-propensity voters to the polls, has run his last campaign.

But 2024’s results will provide plenty of fuel for Democratic angst in the days to come.

The Harris campaign itself believes she lost to Trump because she was facing a restive public angry over the economic and social turbulence in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic.

“You stared down unprecedented headwinds and obstacles that were largely out of our control,” campaign chair Jen O’Malley Dillon wrote in a letter to her staff. “The whole country moved to the right, but compared to the rest of the country, the battleground states saw the least amount of movement in his direction. It was closest in the places we competed.”

Moses Santana, a Puerto Rican living in Philadelphia, is from a demographic which seemed reliably Democratic a decade or so ago. But when he spoke to the BBC this week, he was not so convinced the Democrats had delivered when in power – or that their message today connected with Americans like him.

“You know, Joe Biden promised a lot of progressive things, like he was going to cancel student debt, he was going to help people get their citizenship,” he said. “And none of that happened. Donald Trump is bringing [people] something new.”

- Seven things Trump says he will do in power

- When does he become president again?

- What happens to his legal cases now

- How he pulled off an incredible comeback