Backlash from councils over Rayner housing targets

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLocal councils have told the government its flagship plan to build 1.5m new homes in England over the next five years is “unrealistic” and “impossible to achieve”, the BBC can reveal.

The vast majority of councils expressed concern about the plan in a consultation exercise carried out by Angela Rayner’s housing department earlier this year.

The responses, obtained by the BBC through Freedom of Information laws, potentially set local authorities on a collision course with Labour over one of its top priorities.

The government has said it will respond to the consultation and publish revisions before the end of the year.

Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer has put housebuilding at the heart of the government’s mission to kickstart economic growth and tackle the housing crisis.

But it relies on local authorities adopting targets for new privately-built housing developments in their areas.

Many councils accept the need for more new homes – but they are concerned about whether the targets handed to each of the 317 authorities in England are realistic or achievable.

The concerns are shared by Labour, Conservative and Liberal Democrat authorities, according to BBC analysis of 90% of the consultation responses.

Many fear the algorithm used to calculate the targets has not taken into account strains on local infrastructure, land shortages, and a lack of capacity in the planning system and construction industry.

Labour-run Broxtowe council in Nottinghamshire described the proposed changes as “very challenging, if not impossible to achieve”.

South Tyneside, another Labour-run council, said the plans were “wholly unrealistic”, while the independent-run council in Central Bedfordshire, said the area would be left “absolutely swamped with growth that the infrastructure just can not support”.

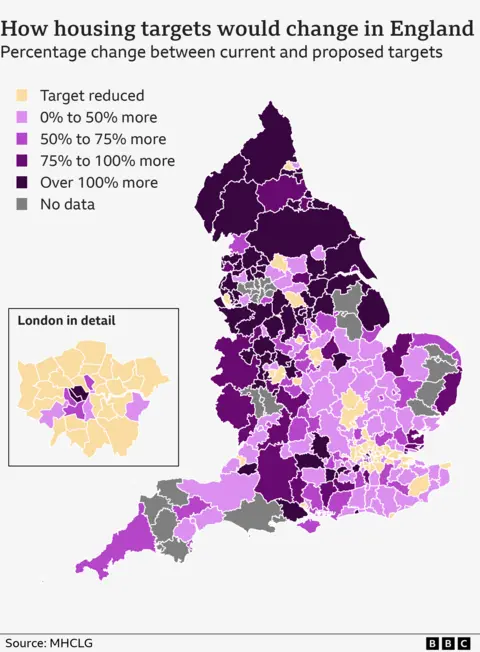

In some cases, the housing targets are radically different to those set by the previous government, with rural areas expected to shoulder more of the burden than inner city authorities. Some parts of London have seen their targets go down.

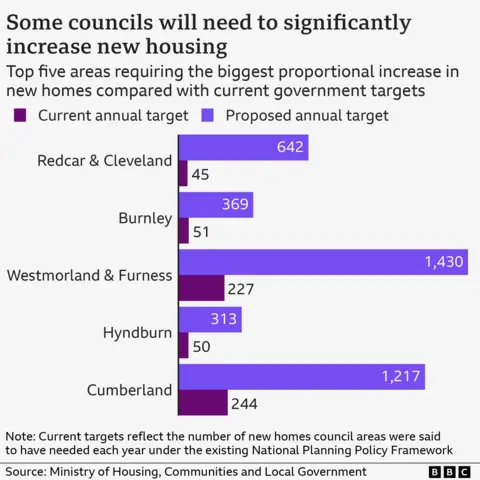

In rural West Lancashire, the yearly housing target for the Labour-run borough council would jump from 166 new dwellings to 605 under the proposed new system.

Deputy leader Gareth Dowling agrees with the general need for more housebuilding after “years of stagnation”, but said his area was already building its “fair share”.

“I don’t think the land is actually available here to build that much housing on,” he said, “unless you were to go and build specifically on arable farmland”.

Dowling claimed the new way of determining targets would not match the housing need in West Lancashire either and called on ministers to “have a look at the responses” to the consultation “and see what’s been said”.

Current housing targets are largely based on projections about how many people will live in a local area in the coming years.

Instead of regularly updating targets whenever these projections changed, the last Conservative government chose to lock in housing targets based on projections made in 2014.

The Labour government claims this has led to targets that would not solve the country’s current housing crisis or provide significant economic growth.

They want the targets for new homes to be based on the current number of houses in an area and how affordable those properties are, rather than the number of people expected to be living there in years to come.

It’s that change in methodology which has led Dowling to claim the new targets will not match housing need, a worry echoed in urban areas.

Thirty miles east, in the city of Salford in Greater Manchester, the Labour-run local authority has warned the government that its approach “loses any connection with future demographic change and is divorced from need”.

The city’s mayor Paul Dennett told the BBC sensible housebuilding plans should not be based just on numbers.

“It’s about looking at your housing waiting list,” he said, “it’s about looking at the impacts around homelessness and rough sleeping, and building the homes that communities and residents need.”

He called on the government not to “control this agenda from Westminster and Whitehall”, and allow more flexibility in the new system so councils can consider specific issues in their area.

Councils are responsible for granting planning permission for new homes – but they mostly rely on the private sector to build the properties, something many local authorities said the government’s new targets did not take into account.

Neil Jefferson, the chief executive of the Home Builders Federation, told the BBC the planning changes were “very positive”.

But he said ministers needed to “do more to support prospective buyers”, give greater access to “suitable” mortgages, and ensure that local authority planning departments “have sufficient capacity to process applications”.

Labour has warned it is willing to overrule local councils’ objections to achieve its aim of delivering 1.5m homes by 2029, underlining the importance it places on housebuilding for economic growth.

Many local authorities that took part in the consultation supported the principle of building more homes and a small number were in favour of the specific plans put forward by the government.

In Oxford, the city council hopes the ambitious new targets will lead to the extra housing that councillors say the area needs.

The planned changes would see Oxford having to build an additional 24,000 homes.

Louise Upton, the local cabinet member for planning, said the council could accommodate 10,000 of those, and that it hoped the new rules would make it more likely that surrounding councils would take on the other 14,000 and allow the city to expand.

“When you are a tightly constrained city like ours is, actually bursting at the seams, you need your surrounding districts to collaborate with you to get the housing that you need,” she said.

“So I think the government’s plan for these new homes is ambitious, but it is achievable. It has to be achievable.”

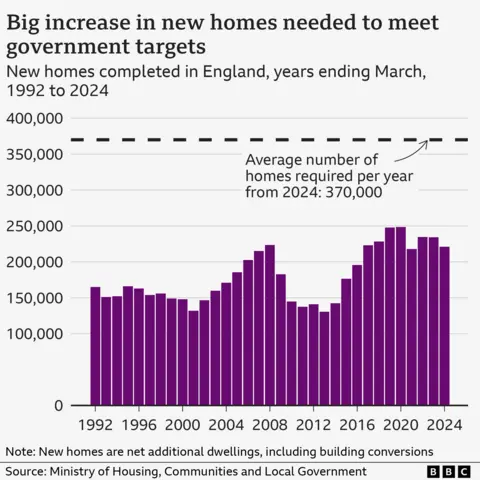

In July, Housing Secretary and Deputy Prime Minister Angela Rayner told MPs the government would be even more ambitious than first anticipated, and would “rise from some 300,000 a year to just over 370,000 a year”.

If all councils hit that target, it would result in significantly more homes than the 1.5m pledge that the government has made.

But last Wednesday, housing minister Matthew Pennycook told a select committee the government would not be imposing national annual targets in the way suggested by Rayner.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said: “This is the worst housing crisis in living memory, and in order to fix this we need to build 1.5 million homes.

“That’s why we have introduced mandatory housing targets for councils and laid out clear plans to support their delivery, including by changing planning rules to allow homes to be built on grey belt land and recruiting 300 additional planning officers.”

The Local Government Association has called on the government to “give councils the tools we need to help build these much-needed new homes”.

Adam Hug, the LGA’s housing spokesman, added that “any national algorithms and formulas would strongly benefit from local knowledge” provided by the people who “know their areas best”.

Graphics by Daniel Wainwright