Why 2025 promises plenty of political fireworks

Reuters

ReutersPolitics in 2025 will be dominated by a single controlling thought: do things start feeling any better?

The answer to that will drive much else in the political conversation: the fortunes, mood and demeanour of the government, the revival or otherwise of the Conservatives and the prominence or otherwise of everyone else.

2024 was a year of spectacular success for Labour, but their landslide general election win already feels like it was ages ago with the new government taking on a tricky inheritance and garnishing it with some foul-ups of their own.

And we head into 2025 with quite the assembly of cocktail ingredients – a flatlining economy, an impatient electorate and a volatile world.

Within weeks, we’ll see the inauguration of Donald Trump.

An already unpredictable international backdrop – from Ukraine to the Middle East – collides with the most unpredictable man ever to occupy the Oval Office.

The implications for trade, for climate change policy, for war and for peace are huge.

The prime minister, stung by the social media moniker that he is “never here Keir” because he is forever on the international circuit, will inevitably find his attention again drawn to the global stage, while making an argument that it has a direct impact on millions of lives in the UK.

There are two inalienable truths in politics that bear repeating: governing is difficult and assembling an electable opposition is difficult.

And perhaps never more so than now, on both counts.

Governing in the 2020s is a pretty unforgiving business – just ask the last PM, Rishi Sunak, or Starmer.

Among Sir Keir’s ministers, I pick up two recurring sentiments about the party’s first six months in power.

The first – and you can still see it in the eyes of ministers when they reflect upon their work – is an excitement after years in the wilderness of opposition that they now have power, and are called upon to make decisions every day.

But the second is a frustration at too many mistakes.

One minister told me they were fed up at what they saw as lacklustre presentation and communication, particularly of difficult stuff like taking the winter fuel payment away from millions of pensioners.

Another acknowledged it had taken them and fellow ministers a while to step up from being administrators, getting a grip of their new jobs and getting used to taking decisions, to being senior politicians in government and taking decisions in a wider, strategic context.

“We are no longer the political wing of the civil service,” observed one Labour backbencher on that learning curve for the new government, which included the brutal removal of the prime minister’s first chief of staff, Sue Gray, not long after I was leaked private details of her salary.

Politics at Westminster feels much more competitive than the numbers suggest it should: Labour’s mountainous majority means they will rarely feel even a marginally quickened pulse when it comes to Commons votes.

But one of the cliches of 2024, because it is true, is Labour’s support feels broad but shallow.

They won a landslide majority with just 34% of the vote, a lower vote share than any party forming a post war majority government.

Opinion polling and approval ratings for both Labour and Sir Keir have taken a hammering since they were elected.

PA Media

PA MediaSo what of the Conservatives and their new leader Kemi Badenoch?

They have been more chipper and more united than they might have been, given just how big a defeat they went down to back in July.

But privately many Tories fear they have not yet hit rock bottom.

They look ahead, but do not look forward, to the local elections in England, in May, where plenty of Tories reckon they will go backwards.

This is because the seats being contested were last fought in 2021, a high point for Boris Johnson after the pandemic, so they have plenty of seats to lose.

Senior Tories tell me privately they reckon Badenoch has made a middling start in the toughest of jobs.

Even her supporters acknowledge they are relieved she hasn’t done or said anything that has rebounded on her, given she has something of a reputation for putting her foot in her mouth now and again.

And they hope she will shake off a scepticism, bordering on suspicion, of journalists and get out more in the new year to make their case.

And they will need to, because the word you hear rather often from Conservative MPs is…

Reform.

The name of Nigel Farage’s party, Reform UK, sends shivers down many a Tory spine, and Labour aren’t immune to concerns about them either.

Farage and his team are upbeat and talk in public and in private about their ambition of winning the next general election.

That seems a fantastical proposition for an upstart outfit whose entire parliamentary party – five MPs – could fit in the back of a taxi.

But remember they attracted 4.1 million votes at the general election, 600,000 more than the Liberal Democrats.

The issue Reform had was their votes were spread out, rather than piling up in sufficient numbers in particular places to win many seats.

In 2025, it will be worth keeping an eye on two men within Reform – the chair, Zia Yusuf, and the new Treasurer, Nick Candy.

They personify Nigel Farage’s twin aims for his party – getting more organised and generating money.

The party is trying to build local branches around the country, local nerve centres of enthusiasm that could be the building block for winning more seats at local elections, at devolved elections (coming in Scotland and Wales in 2026) and at the next general election.

Expect to see a blitz of regional conferences in the opening weeks of the new year to try to drive this growth.

Stuart Mitchell

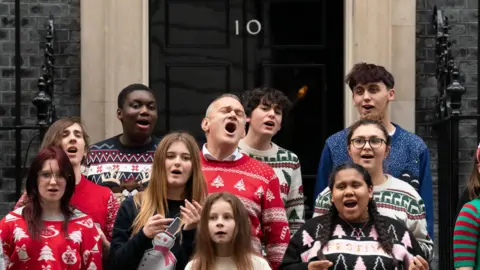

Stuart MitchellThe Lib Dems had a corker of a 2024.

They won beyond their dreams and Sir Ed Davey now leads a party of 72 MPs.

Sir Ed remains determined to do politics with a smile – take his Christmas single as the latest example of that – and trying to own the issues of social care, young carers and the health service.

The party is trying to maximise the exposure their status as Westminster’s third party gives them – Sir Ed went on Have I Got News For You recently, for instance, although invites like that can prove awkward.

In the next few weeks, don’t be surprised if he pops up talking about foreign affairs and outflanks the broadly pro-European noises we’ve heard from Labour by talking about a potential UK future back inside the European Union’s customs union.

The party also has an optimistic eye on the local elections in May, particularly in counties such as Devon, Surrey, Shropshire and Wiltshire.

The challenge for Sir Ed will be converting a much bigger parliamentary party into influence in an era of a big majority government and noisy fellow opposition parties.

PA Media

PA MediaThe SNP had a dreadful 2024: nearly nuked in the general election by the rampant return of Labour in Scotland.

But speaking to senior figures as the year drew to a close, their mood was less bleak than it might have been.

The row over so-called Waspi women and Labour maintaining the two child benefit cap are just two examples where the SNP hope to point to clear differences between them and Labour, in the countdown to elections to the Scottish Parliament in 2026.

Green MPs around Westminster wear plenty of smiles as we head into 2025.

For a start we now say Greens plural when talking about them – for the first time there is more than one of them.

They have seen their party membership swell to around 60,000 and they are hoping too to swell their presence on councils in those English local elections in May.

Senior figures point out that they are currently part of the administration in over 10% of councils in England and Wales and finished second behind Labour in 40 seats at the general election.

In some of those places they are miles behind, but in others there is at least the chance that they might be able to capitalise over time on disgruntlement with Labour and lure voters on Labour’s Left in their direction. Let’s see.

And don’t forget Plaid Cymru; the parliamentary group known as the Independent Alliance, which includes the former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn; and the parties of Northern Ireland, all of whom have their own concerns and campaigns – and can cause ructions for ministers inside and outside Parliament.

Here goes with politics in 2025.

It might not be a general election year.

But I reckon it will be lively.