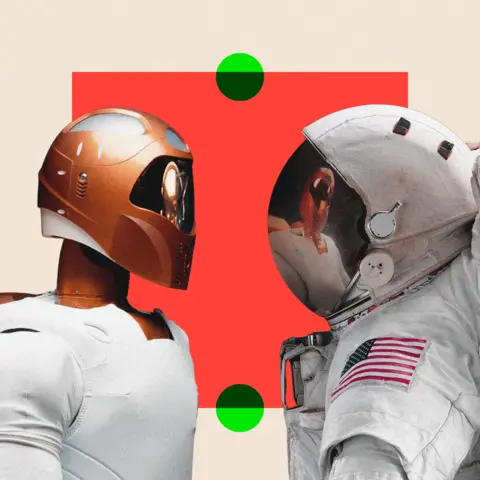

Could AI robots replace human astronauts in space?

BBC

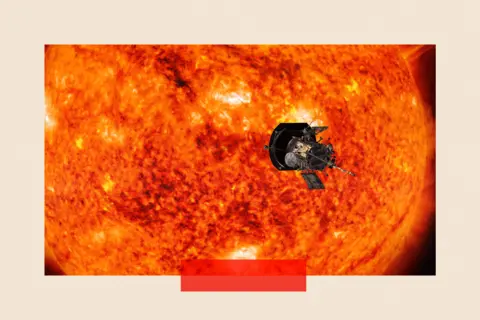

BBCOn Christmas Eve, an autonomous spacecraft flew past the Sun, closer than any human-made object before it. Swooping through the atmosphere, Nasa’s Parker Solar Probe was on a mission to discover more about the Sun, including how it affects space weather at Earth.

This was a landmark moment for humanity – but one without any human directly involved, as the spacecraft carried out its pre-programmed tasks by itself as it flew past the sun, with no communication with Earth at all.

Robotic probes have been sent across the solar system for the last six decades, reaching destinations impossible for humans. During its 10-day flyby, the Parker Solar Probe experienced temperatures of 1000C.

But the success of these autonomous spacecraft – coupled with the rise of new advanced artificial intelligence – raises the question of what role humans might play in future space exploration.

NASA

NASASome scientists question whether human astronauts are going to be needed at all.

“Robots are developing fast, and the case for sending humans is getting weaker all the time,” says Lord Martin Rees, the UK’s Astronomer Royal. “I don’t think any taxpayer’s money should be used to send humans into space.”

He also points to the risk to humans.

“The only case for sending humans [there] is as an adventure, an experience for wealthy people, and that should be funded privately,” he argues.

Andrew Coates, a physicist from University College London, agrees. “For serious space exploration, I much prefer robotics,” he says. “[They] go much further and do more things.”

NASA

NASAThey are also cheaper than humans, he argues. “And as AI progresses, the robots can be cleverer and cleverer.”

But what does that mean for future generations of budding astronauts – and surely there are certain functions that humans can do in space but which robots, however advanced, never could?

Rovers verses mankind

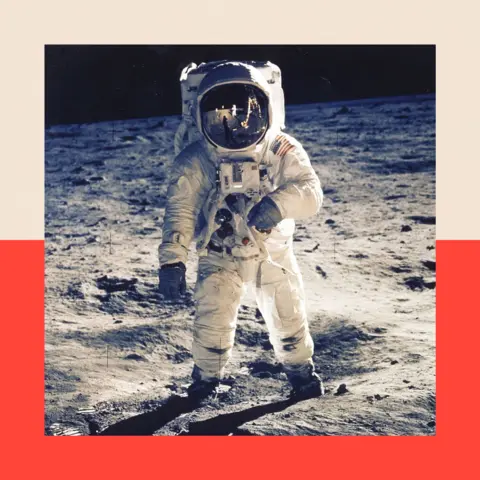

Robotic spacecraft have visited every planet in the solar system, as well as many asteroids and comets, but humans have only gone to two destinations: Earth’s orbit and the Moon.

In all, about 700 people have been to space, since the earliest in 1961, when Yuri Gagarin from the then-Soviet Union became the first cosmic explorer. Most of those have been into orbit (circling the Earth) or suborbit (short vertical hops into space lasting minutes, on vehicles like the US company Blue Origin’s New Shepard rocket).

“Prestige will always be a reason that we have humans in space,” says Dr Kelly Weinersmith, a biologist at Rice University, Texas and co-author of A City on Mars. “It seems to have been agreed upon as a great way to show that your political system is effective and your people are brilliant.”

But aside from an innate desire to explore, or a sense of prestige, humans also carry out research and experiments in Earth’s orbit, such as on the International Space Station, and use these to advance science.

NASA

NASARobots can contribute to that scientific research, with the ability to travel to locations inhospitable to humans, where they can use instruments to study and probe the atmospheres and surfaces.

“Humans are more versatile and we get stuff done faster than a robot, but we’re really hard and expensive to keep alive in space,” says Dr Weinersmith.

In her 2024 Booker Prize-winning novel Orbital, author Samantha Harvey puts it more lyrically: “A robot has no need for hydration, nutrients, excretion, sleep… It wants and asks for nothing.”

But there are downsides. Many robots are slow and methodical – for example on Mars, the rovers (remote-controlled motor vehicles) trundle along at barely 0.1mph.

“AI can beat human beings at chess, but does that mean they’ll be able to beat human beings in exploring environments?” asks Dr Ian Crawford, a planetary scientist at the University of London. “I just don’t think we know.”

He does, however, believe that AI algorithms might enable rovers to be “more efficient”.

AI assistants and humanoid robots

Technology can play a part in complementing human space travel by freeing up astronauts from certain tasks to allow them to focus on more important research.

“[AI could be used to] automate tedious tasks,” explains Dr Kiri Wagstaff, a computer and planetary scientist in the US who previously worked at Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. “On the surface of a planet, humans get tired and lose focus, but machines won’t.”

The challenge is that vast amounts of power are needed to operate systems like large language models (LLM), which can understand and generate human language by processing vast amounts of text data. “We are not at the point of being able to run an LLM on a Mars rover,” says Dr Wagstaff.

“The rovers’ processors run at about a tenth [of the speed] that your smartphone has” – meaning they are unable to cope with the intense demands of running an LLM.

Complex humanoid machines with robotic arms and limbs are another form of technology that could take on basic tasks and functions in space, particularly as they more closely mimic the physical capabilities of humans.

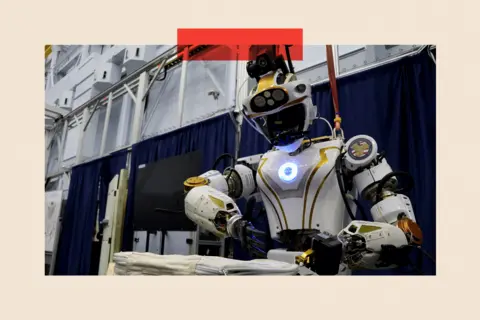

NASA

NASANasa’s Valkyrie robot was built by the Johnson Space Center to compete in a 2013 robotics challenge trial. Weighing 300lb and standing at 6ft2in, it looks not unlike a Star Wars Stormtrooper, but it is one of an increasing number of human-like machines with superhuman abilities.

Long before the Valkyrie was created, Nasa’s Robonaut was the first humanoid robot designed for use in space, taking on tasks that were otherwise performed by humans.

Its specially designed hands meant it could use the same tools as astronauts and carry out complex, delicate tasks like grasping objects or flicking switches, that were too challenging for other robotic systems.

A later model of the Robonaut was flown to the International Space Station on the space shuttle Discovery in 2011, where it helped with maintenance and assembly.

Reuters

Reuters“If we need to change a component or clean a solar panel, we could do that robotically,” says Dr Shaun Azimi, lead of the dexterous robotics team at Nasa’s Johnson Space Center in Texas. “We see robots as a way to secure these habitats when humans aren’t around.”

He argues that robots could be useful, not to replace human explorers but to work alongside them.

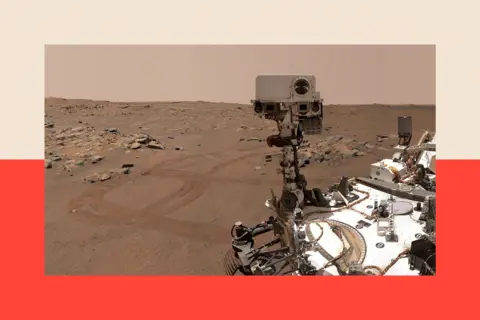

Some robots are already working on other planets without humans, sometimes even making decisions on their own. Nasa’s Curiosity rover, for example, is exploring a region called Gale Crater on Mars and autonomously performs some of its science without human input.

“You can direct the rover to take pictures of a scene, look for rocks that might fit science priorities for the mission, and then autonomously fire its laser at that target,” says Dr Wagstaff.

“It can get a reading of a particular rock and send it back to Earth while the humans are still asleep.”

NASA

NASABut the capabilities of rovers like Curiosity are limited by their slow pace. And there is something else they cannot compete with too. That is, humans have the added bonus of inspiring people back on Earth in a way that machines cannot.

“Inspiration is something that is intangible,” argues Prof Coates.

Leroy Chiao, a retired Nasa astronaut who went on three flights to space in the 1990s and 2000s on Nasa’s Space Shuttle and to the International Space Station, agrees. “Humans relate when humans are doing something.

“The general public is excited about robotic missions. But I would expect the first human on Mars to be even bigger than the first Moon landing.”

Life on Mars?

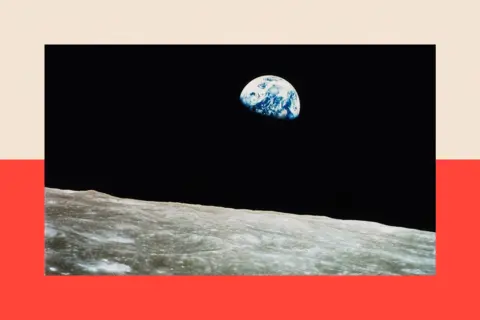

Humans have not travelled further than Earth’s orbit since December 1972, when the last Apollo mission visited the Moon. Nasa is hoping to return humans there this decade with its Artemis programme.

The next crewed mission will see four astronauts fly around the Moon in 2026. A further mission, scheduled for 2027, will see Nasa astronauts land on the Moon’s surface.

Reuters

ReutersThe Chinese space agency, meanwhile, also wants to send astronauts to the Moon.

Elsewhere Elon Musk, CEO of the US company SpaceX, has his own plans related to space. He has said that his long-term plan is to create a colony on Mars, where humans could land.

His idea is to use Starship, a vast new vehicle that his company is developing, to transport up to 100 people there at a time, with the aim for there to be a million people on Mars in 20 years.

“Musk is arguing we need to move to Mars because that could be a backup for humanity if something catastrophic happens on Earth,” explains Dr Weinersmith. “If you buy that argument, then sending humans into space is necessary.”

However, there are large unknowns about living on Mars, including myriad technical challenges that she says remain unsolved.

“Maybe babies can’t develop in that environment,” she says. “There [are] ethical questions [like this] that we don’t have the answers to.

“I think we should be slowing down.”

Lord Rees has a vision of his own, though, in which human and robotic exploration might merge to the point that humans themselves are part-machine to cope with extreme environments. “I can imagine they will use all of the techniques of genetic modification, cyborg add-ons, and so on, to cope with very hostile environments,” he says.

“We may have a new species that will be happy to live on Mars.”

Until then, however, humans are likely to continue their small steps into the cosmos, on a path long trodden by robotic explorers before them.

Top image credit: NASA

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think – you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.