Sid, Senna and an F1 revolution

- Published

As Gary Hartstein stood alongside Professor Sid Watkins, leaning on the roof of the medical car they shared, he was struggling to find the right words.

The pair were waiting for practice to begin for the 1994 Belgian Grand Prix.

Spa-Francorchamps had been tweaked from the previous year – a chicane had been introduced at Eau Rouge to slow the field. The grid was not the same as at the start of the season either; a young David Coulthard now partnering Damon Hill at Williams.

And the atmosphere between the friends had changed, too.

“There was a huge elephant in the car,” Hartstein tells BBC Sport.

The unspoken was almost unspeakably sad.

Four months before, Watkins – Formula 1’s first full-time doctor, a neurosurgeon and the sport’s medical delegate – tried to save two drivers, who died on successive days at Imola. The first was Roland Ratzenberger. The second was Ayrton Senna, the sport’s superstar and a family friend of Watkins.

Hartstein gently probed, asking Watkins how he was. The Englishman’s reply astounded him.

“He tells me the story of when he felt Ayrton’s soul leave his body,” Hartstein says.

“He’s resuscitating this guy who he’s deeply, deeply linked to – this is like resuscitating your kid.

“It was one of those moments of very powerful humility for me. This guy was sharing something with me that is so personal.

“And then he rolled up his sleeves and got to work.”

Senna qualified on pole position for the first two races of the 1994 season, but failed to finish either, before heading to Imola

When Watkins arrived in F1 in 1978, death was a regular occurrence – at least one driver would be killed while racing most years.

Watkins’ work was to reduce that fatality rate.

He had been hired by Bernie Ecclestone, then the owner of the Brabham team and chief executive of the Formula One Constructors’ Association.

He had telephoned Watkins at the London Hospital and asked to see him later that day. Watkins was part of the medical panel that provided cover at the British Grand Prix, but it was the first time the pair had spoken.

Ecclestone, who had once carried the helmet of his good friend Jochen Rindt back to the pits after a fatal crash, introduced himself and explained the failings in medical safety at circuits.

Watkins, a car enthusiast with a taste for adventure, agreed to take on the challenge.

Wheels had been part of Watkins’ life from an early age. He was born in Liverpool in 1928 and his father ran Wally Watkins’ Bike Shop in Bootle. There was also a family garage where the young boy worked alongside his dad, “pumping petrol, fiddling with cars and doing mechanics’ work”.

After qualifying at the University of Liverpool’s Medical School and a stint in the United States, Watkins returned to the UK in 1970 to become the first professor of neurosurgery at the London Hospital.

Within weeks of his first meeting with Ecclestone, Watkins was attending the Swedish Grand Prix in his new role as F1 surgeon, combining it with his day job.

At the Anderstorp circuit, Watkins found there was no helicopter provided for practice because it was not considered dangerous compared with the race.

He would soon become accustomed to the haphazard nature of safety arrangements within F1.

At Brands Hatch for the British Grand Prix, he was faced with a small, ill-equipped medical centre staffed by two ambulanceman drinking beer.

But at least there was a medical centre. At the next race in Germany, at Hockenheim, the emergency facility was a converted single-decker bus, with its staff camping in tents nearby.

It reflected a culture within the sport which seemed to accept death as an occupational hazard.

“When Sid arrived in the sport, life was cheap,” Hill, Senna’s team-mate at Williams when he died in 1994, tells BBC Sport.

“Drivers were seen as risk-takers and playboys. The fatalities were just part of the price for having a good time, really.”

Hartstein, who worked full-time alongside Watkins as his deputy from 1997 and succeeded him in 2005, agrees.

“When Sid was asked by Bernie to come in, things were fairly dreadful and had been dreadful for a long time,” he says.

Watkins acted quickly, telling Ecclestone circuits should not hold F1 races unless they had properly equipped medical centres. He asked that he and an anaesthetist be allowed to follow the first lap of a race in a fast car equipped with a radio and “driven by a competent, recognised race driver who knew the circuit”.

He also stipulated that helicopters should be available for all practices, the warm-up and the race.

Less than three months after attending his first grand prix in his new role, Watkins saw first hand the urgent need to change mindsets and improve safety measures.

After a huge first-lap crash at the 1978 Italian Grand Prix, police formed a line across the track and would not let him past. On the other side of the cordon Swedish driver Ronnie Peterson was trapped in his wrecked Lotus with serious leg injuries. After significant delays in getting him free and treated by medics, Peterson died from an embolism the following morning.

Watkins was subsequently given responsibility for supervising and being actively involved in rescue arrangements at circuits.

“Because this had never happened before, because this never existed before, it was incredibly hard,” Hartstein says. “Doctors around the circuit, deployed in a certain way with a certain level of competency, ambulances, referral hospitals – the whole system that we take so for granted now, he had to create that.

“There was no culture for that. There were the silly arguments: ‘Well, people come to see the deaths and that’s part of the attraction, and the drivers understand that, they’re consenting.’

“The first and hardest battle was to change mentality. His job was rendered difficult by recalcitrant culture.”

Gary Hartstein (left) and Sid Watkins pose at the 2010 British Grand Prix. Hartstein succeeded Watkins as Formula 1’s chief doctor in 2005.

To change cultures, it helps to have charisma. And Watkins had it in spades.

Fond of a cigar – he had a pocket to store them in his fireproof overalls – a glass of wine, and a good story, he was a familiar figure in the paddock.

“The Formula 1 circus was his practice,” says Watkins’ son Alistair.

“He was totally accessible – anyone could ask him anything.”

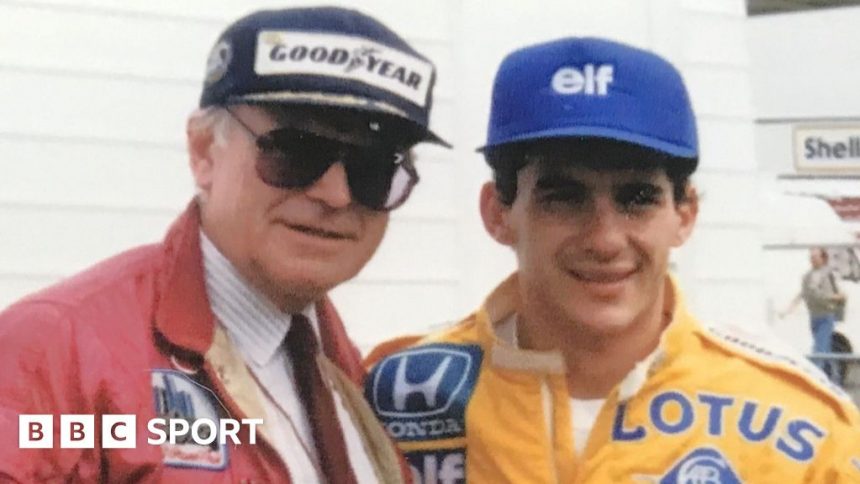

During his time working in F1, Watkins formed strong friendships with a number of the drivers but had what he described in his 1996 book Life at the Limit as an “unusual bond” with Senna.

Watkins stayed at Senna’s farm outside Sao Paulo in 1993 where they went fishing together, while the Brazilian joined the Watkins family in Coldstream, in the Scottish Borders, as well as visiting Sid at his flat in London’s Docklands.

“He was like a member of the family, the children adored him,” Watkins’ widow Susan tells BBC Sport.

“I used to make chocolates and cookies, and when Ayrton was there half the cookie jar would disappear.

“We went to the pub for lunch and people looked at him as though ‘it can’t be’.

“We’d all go off to the Chinese restaurants in the East End. Nobody was quite sure whether it was him or not.”

While with the Watkins family in Scotland, Senna was invited to speak at Loretto School in Musselburgh.

Susan says: “He was quite nervous speaking to these boys and of course there was a full turnout of people there and they would stand up and say ‘Sir’, and Ayrton said ‘Please, please don’t call me Sir’.

“He handled it very well. They asked him how he felt about advertising cigarettes on cars. He really gave great answers despite being quite nervous. And of course the boys loved it.

“Afterwards there was a reception at the headmaster’s house and the Bishop of Truro was there and he and Senna went off in the corner and prayed together.”

Senna, on the right of the stage, addresses pupils at Loretto School in Musselburgh during a trip to stay with Watkins and his family

Senna visited a nearby museum dedicated to 1963 and 1965 F1 world champion Jim Clark, a Scot considered one of the greatest drivers of all time. Clark was killed in a crash at Hockenheim in 1968, and Susan remembers that while at the museum Senna “felt very uncomfortable – he said it was like a shrine”.

Asked to describe the relationship between Watkins and Senna, Susan says: “I think father-son. Sid was very paternal to a lot of the boys, the drivers, but he had a special relationship with Ayrton because he was such a nice young man. I don’t think his life was easy. The bond between them, I think he completely trusted Sid and he was comfortable with our family.”

Hartstein believes Senna’s “compassion” and “intellectual curiosity” drew him to Watkins. At qualifying for the 1992 Belgian Grand Prix, Erik Comas had a high-speed accident that left the Frenchman unconscious. Senna, driving his McLaren flat-out, came upon the aftermath and stopped his car, got out and ran over before shutting down Comas’ engine and supporting his head until medical assistance arrived.

Later, Senna sought out Watkins, as Hartstein recalls: “Ayrton left the paddock and came up to the car and asked questions – ‘what happens with the airway? What are my first actions if I’m first at the scene?’

“Sid’s baseline with respect to the drivers was extremely paternalistic – they were his boys and his default with the drivers is that ‘I love them unless they prove themselves unworthy of that love by just being idiots’.

“Ayrton was way, way on the opposite end of that spectrum, A guy who’s going to ask Sid about the medical questions after an accident. The fact that Ayrton felt a duty to care.”

Watkins had a personal and professional duty of care towards Senna, which he could never have felt more strongly than when attempting to save his life at Imola in 1994.

After Ratzenberger’s near-200mph qualifying crash on Saturday, 30 April, a doctor was on the scene within 12 seconds. Resuscitation was attempted and the Austrian was taken to the intensive care unit of the medical centre at the circuit. But, for all Watkins’ innovations and improvements, it was clear the situation was hopeless.

Senna appeared at the door of the centre. He had already been to the scene of the accident and had spoken to marshals but wanted to know more.

Watkins stepped outside to answer his questions. Senna cried on Watkins’ shoulder as he realised Ratzenberger was beyond saving.

Seeing how devastated the Brazilian was, Watkins tried to persuade the 34-year-old Senna to withdraw from the race and give up F1 altogether. “What else do you need to do?” Watkins, then 65, asked him.

“You have been the world champion three times, you are obviously the quickest driver. Give it up and let’s go fishing.”

After a long pause, Senna answered: “Sid, there are certain things over which we have no control. I cannot quit, I have to go on.”

They were the last words Senna spoke to Watkins.

Senna and Watkins in conversation in the wake of Ronald Ratzenberger’s crash. Senna was to die the following day.

The next day, Senna, leading the race in his Williams, lost control at 190mph at the Tamburello corner and crashed into the wall, his helmet pierced by a suspension arm. Watkins was driven at speed to the accident and immediately joined the rescue effort; Senna’s helmet was removed, Watkins got an airway into his mouth and raised his eyelids. Watkins could see from Senna’s pupils that he had a massive brain injury and could not survive.

“Everybody asked me what my emotion was,” said Watkins in 2001 of his final conversation with Senna. “My emotion was that I hadn’t bullied him enough. I so regretted that I hadn’t really bullied him.”

“He had to deal with the gruesome reality of the whole thing,” says Hill.

“That’s almost the worst thing that can happen, isn’t it, to a doctor, is actually having to care for someone who’s a friend of yours, somebody you’ve had very deep conversations with only 12 hours before.

“He was used to gore but, my god, when you’ve just been trying to convince someone that it’s not necessary to be a racing driver, and then you’re trackside trying to save his life when you know there’s nothing you can do, it must have been very difficult.”

Alistair says his dad would “talk about Ayrton quite a bit” and was “hugely upset” by his death, but “then kind of put a brave face on it thereafter”.

“I’d see him reminisce in a sad way about it, but he kept his emotions fairly in check,” says Alistair.

“It was part of his generation, but also as a neurosurgeon he had 30 years of seeing terrible things. I guess learning to deal with the grimmer things in life, eventually as a neurosurgeon you get quite used to it.”

Hill, who was in only his second full season in F1 in 1994 and went on to win the world title two years later, says Watkins “really admired Senna for the kind of person he was”.

He adds: “His famous conversations with Ayrton where he suggested that Ayrton just gave it up and went fishing – he could see that it wasn’t that important, but yet of course he wasn’t Ayrton Senna.

“You just can’t say to someone like Ayrton Senna ‘why don’t you just go fishing?’ That’s the complexity of the man and what drives people to do stuff which seems reckless.”

Senna signs the visitors’ book at the Jim Clark Motorsport Museum in Duns in February 1991 on a trip to visit Watkins

The deaths of Ratzenberger and Senna, during a weekend in which Jordan driver Rubens Barrichello was seriously injured, induced a crisis of confidence.

Watkins’ arrival in the sport, the transformation in the level of medical cover and switch from aluminium to carbon-fibre chassis in the cars had meant F1 had not suffered a death at a race weekend in the 12 years before that fateful San Marino Grand Prix.

Max Mosley, president of motorsport’s governing body the FIA, announced the formation of an expert advisory safety committee and made Watkins its chairman. It was told to assess the design of F1 cars, crash barriers, the configuration of circuits and run-off areas and how to protect people in the pit lane and in public areas.

“Formula 1 was genuinely worried that it would go into a spiral of decline and the car manufacturers would pull out,” says Alistair.

“I think my father really enjoyed that challenge, the safety challenge. That was an intellectual challenge more than anything else. ‘How do we keep the sport exciting but make it safe?’ Everything was looked at. There were some quite small changes that made a massive difference right from the start – padding around the cockpit, raising the cockpit levels, then the Hans [head and neck safety] device came in.”

“Sid was deeply emotionally committed to this goal,” says Hartstein.

“He was a brilliant scientist in his own right so he understood the nature of the scientific process and how data hypothesis can be confirmed or rejected. Deeply, deeply, deeply intelligent. So when engineers present data to Sid, even though this was not his field directly, he immediately understood.

“Sid was agnostic in terms of what the solutions were going to be. He had no skin in the game other than to make this sport safer. He wasn’t an engineer for a team, he wasn’t an aerodynamicist. He was smart enough and curious enough to be able to kind of oversee all of this. And charismatic enough to keep this disparate team, pulling in 15 directions, focused on a goal.”

Hill agrees that Watkins’ shrewd political instinct was key. “Sid understood the power games that were going on, he understood the stresses that drivers were having to deal with and he could employ his scientific brain to problem-solving for the sport,” he says.

Northern Ireland’s Martin Donnelly, Finland’s two-time world champion Mika Hakkinen and Austria’s Gerhard Berger were among the drivers who Watkins helped save through treatment, and his pursuit of safety reforms helped ensure serious injuries became rarer

In the 30 years since Imola, Jules Bianchi – who died as a result of a crash at the 2014 Japanese Grand Prix – is the only driver to have lost his life because of an accident in an F1 race.

As trackside surgeon, Watkins played a major role in saving the lives of several F1 drivers after heavy accidents, among them Ferrari’s Didier Pironi at the 1982 German Grand Prix, Martin Donnelly at the 1990 Spanish Grand Prix, Barrichello at Imola in 1994 and McLaren’s Mika Hakkinen at Adelaide in 1995.

Other drivers were grateful beneficiaries of the safety measures championed behind the scenes.

“I could cite at least 10 accidents that we attended with no injury that would have been fatal if it were not for the barriers, the asphalt, the new helmet,” says Hartstein. “Scores of dead drivers had it not been for this, in F1, the feeder series, F3, even the junior series, for sure. Yeah, scores.”

And F1 was just Watkins’ side project.

He combined this role with being professor of neurology at the London Hospital, alternating working weekends with another consultant to ensure he was ‘off-duty’ for each race.

Hill says a conversation with Watkins, who died in 2012 aged 84, was different compared with anyone else within F1.

“You just basically got the perspective of someone who knew what real values were and what really mattered,” he says. “You can get wrapped up in things you think are important, whether or not you’re being beaten by someone or you’re winning or whatever.

“His perspective on life was ‘you’re all having a great time, and on Monday I’m going back into an operating theatre and I’m going to operate on someone’s brain because they’ve got something much more serious going on’.

“Maybe we didn’t deserve someone of his calibre. He was a key player but in a way that was unusual. It was, in a way, unique. And trailblazing because before that, either nobody cared or the people who did care were told to shut up. And you can’t really tell somebody like Sid to shut up.”

Watkins was described by Formula 1’s governing body – the FIA – as having made “a unique contribution to motorsport” during his life

Related Topics

Previously on Insight

-

-

Published22 April

-

-

-

Published16 April

-

-

-

Published12 April

-

-

-

Published11 April

-

-

-

Published9 April

-