Mycorrhizal fungi are the supply chains of the soil. With filaments thinner than hair, they shuttle vital nutrients to plants and tree roots.

In return, the fungi receive carbon to grow their networks. In this way, 13 billion tons of atmospheric carbon dioxide — one-third of fossil-fuel emissions worldwide — enter the soil each year.

These fungi cannot live on their own; they need the carbon from plants. In turn, 80 percent of the world’s plants rely on fungal networks to survive and thrive. The two are dependent trade partners.

These fungi make uncannily smart choices, even without a brain or central nervous system. Scientists describe them as “living algorithms.”

The trade algorithms reward efficiency: Build the most lucrative pathway possible for the lowest construction cost.

Fungal networks appear to assess demand and supply. Which plants need its nutrients the most? Which offer the most carbon? Where is the optimal payoff? This analysis shapes how the networks expand, as scientists learned when they mapped the growth in real-time.

“Fungi are super clever,” said Toby Kiers, an evolutionary biologist at the Free University of Amsterdam. “They’re constantly adapting their trade routes. They’re evaluating their environment very precisely. It’s a lot of decision-making.”

How do fungi do it? To find out, Dr. Kier and her colleagues grew fungi in hundreds of petri dishes, or “fungal arenas.”

Then, with an imaging robot, the team tracked the growth of the networks nonstop for days, measuring how the organisms reshaped their trade routes in response to different conditions. Their study was published on Feb. 26 in the journal Nature.

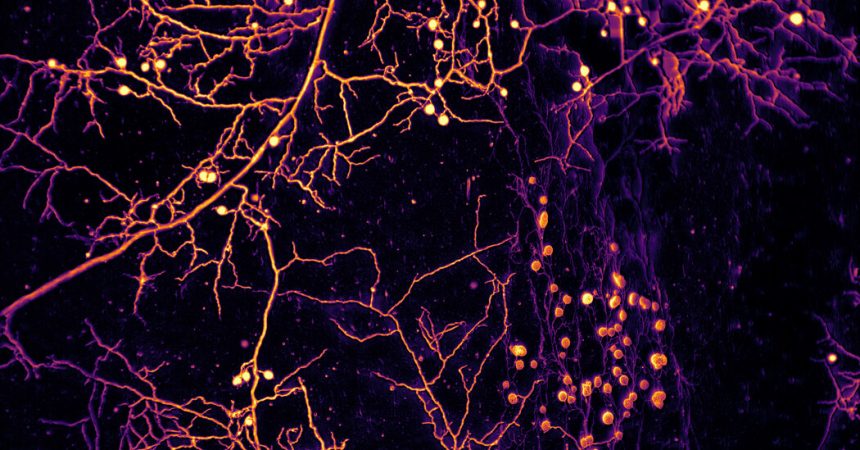

From special nodes, or growing tips, the fungi deploy filaments that explore and assess new territory. Over several days, the scientists labeled and monitored a half-million new nodes and mapped the expansion.

The growth revealed fungal decision-making in action. For instance, the team learned, a fungus will forgo trading with nearby plants in favor of more distant ones if the return in carbon is greater.

Fungal networks are sometimes described as the soil’s circulatory system.

But in fungal networks the flow is open. Carbon, nitrogen, phosphorus, water and even fungal nuclei move in either direction, even in opposite directions at once.

“That’s physically mind-boggling,” said Tom Shimizu, a biophysicist at AMOLF, a physics institute in Amsterdam, and whose lab built the robot. The fungus, he said, “is basically a microbe that plays economic games. How do you do that if you’re just a tube of fluid flowing?”

They do it by obeying some basic local rules, it turns out. As the growing tips progress, new branches form behind them at a steady rate. But when one tip hits another, they fuse and form a loop.

This removes dead ends, avoids wasteful expansion and keeps resources moving quickly on the main highways. The edge of the fungal network expands like a ripple, laying down an efficient trading nexus as it goes.

Scientists still want to understand how fungi move so much carbon so far without clogging the pipes. And they hope to simulate how these ancient organisms respond to wildfires, drought and other disruptions from climate change. “We’re trying to figure out how they play the games they play,” Dr. Shimizu said.

Credits: Corentin Bisot – AMOLF/VU Amsterdam; Loreto Oyarte Gálvez – VU Amsterdam/AMOLF; Rachael Cargill – VU Amsterdam/AMOLF; Vasilis Kokkoris – VU Amsterdam/AMOLF/SPUN; Joe Togneri/SPUN; Loek Vugs.

Produced by Antonio de Luca and Elijah Walker.