Benin and other West African nations imposed sanctions on Niger, including border closures, in a bid to force the military to hand back power to the elected government.

The sanctions by the Economic Community of West African States (Ecowas) were eased in February, and were expected to normalise trade relations with Niger.

But Niger refused to open its land border for goods coming from Benin.

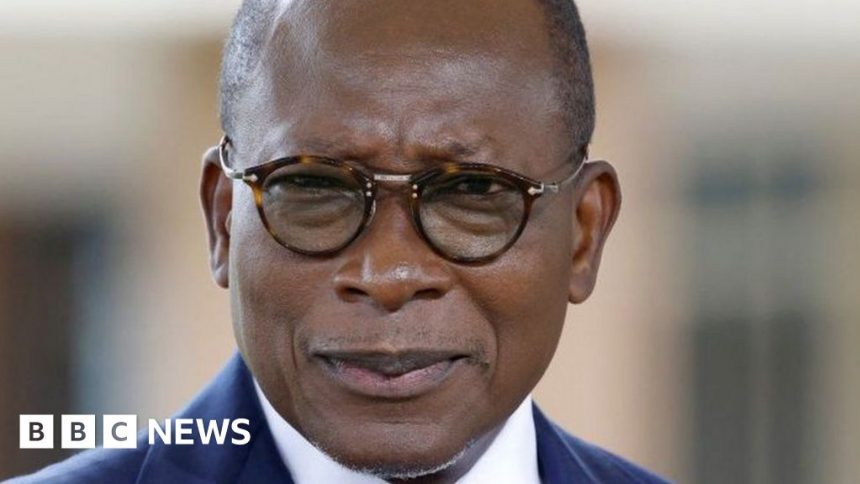

Mr Talon has accused Niger of not co-operating to restore ties.

“If you want to load your oil in our waters, you must consider that Benin is not an enemy country and that [its] territory cannot be the subject of illicit trafficking or informal exchange,” he said on Wednesday.

“If tomorrow the Nigerien authorities decide to collaborate with Benin in a formal manner, the boats will be loaded,” he added.

Niger’s junta has not yet responded to his comments.

Benin’s move puts at risk Niger’s plan to begin exporting oil – the landlocked country has been producing about 20,000 barrels per day primarily for domestic consumption due to the lack of an export route.

Following the completion of a 2,000km-long (1,240 miles) Chinese-built pipeline through Benin, production was set to rise significantly to 110,000 barrels.

The dispute is seen as undermining the project and affecting relations between two countries that were close trade partners before the coup in Niger.

Herve Akinocho, the director of the Centre for Research and Opinion Polls in Benin, said the country would lose about $7m (£5.6m) daily from oil transit fees that Niger would have paid.

He told the BBC Newsday radio programme that Benin was suffering bigger losses from Niger’s decision to keep the border shut.

He said that most of Niger’s imports and exports passed through Benin before the coup, but this was now happening through Togo.

He said that Niger’s refusal to open the border was “really hitting the economy of Benin [including] the transport sector”.